Goodshaw Chapel is a rare surviving example of an early Protestant dissenter place of worship. Built by its own congregation in what was once a remote spot, it is intimately connected to a group known as the Larks of Dean. This was a collection of local musicians whose compositions and relentless eagerness to play left a legacy of original music.

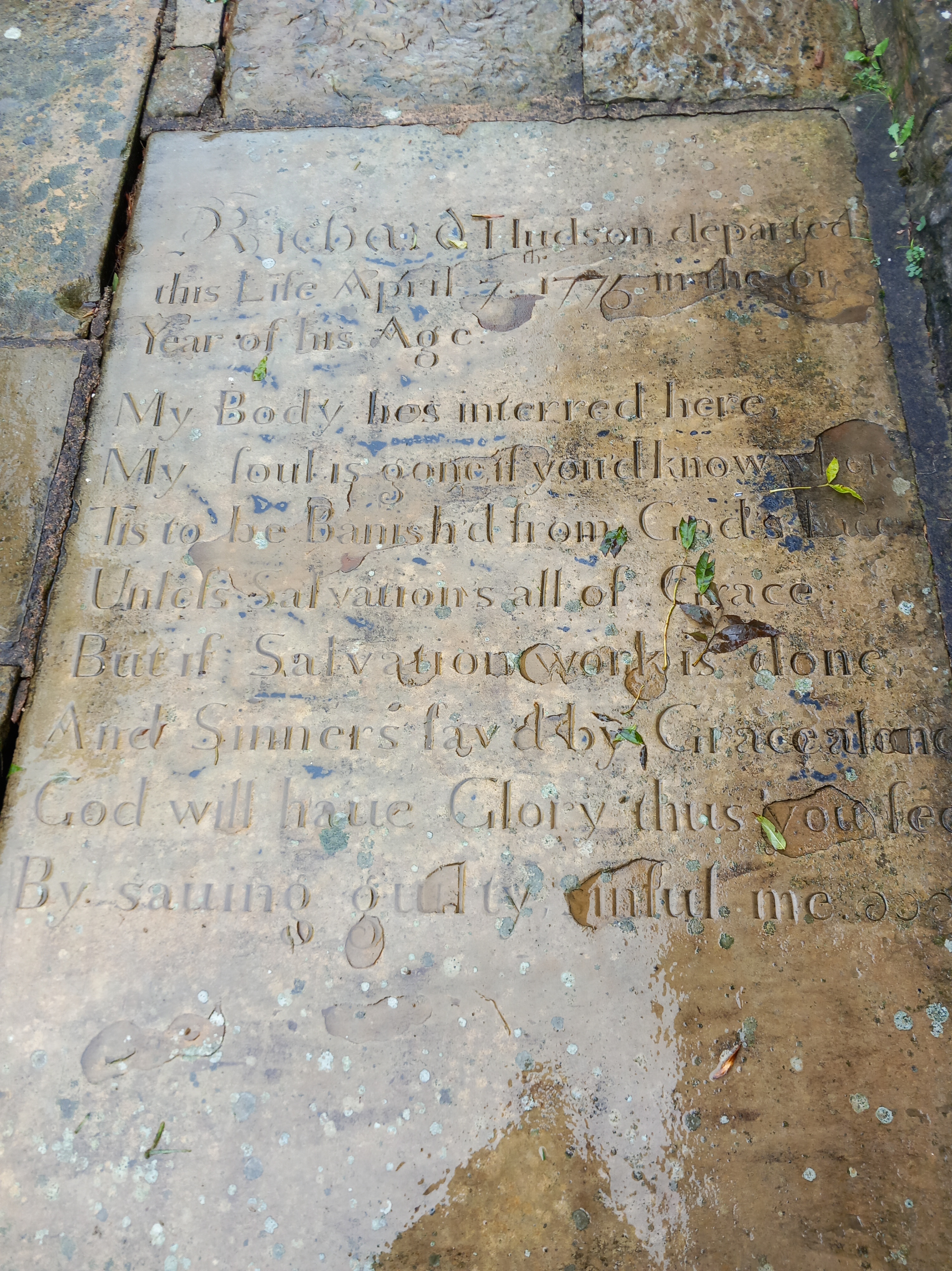

In 1742, records show that local Baptists would meet in farmhouses and cottages in the villages of Lumb, Dean and Whitewell Bottom. John Nuttall, an itinerant preacher from Bacup, who travelled around the countryside on horseback, was the original minister of the group. Both Nuttall and another preacher called Richard Hudson had a shared love of new religious music. The group they set up would become known as the Larks of Dean. Hudson and Nuttall married the Grindrod sisters of Yorkshire, both reputed to be excellent singers.

The congregation’s numbers were soon swelled by the addition of a group of Wesleyan Methodists. In 1753, they built a meeting house at Bullar Trees near Lumb, but after just seven years it proved to be too small for the numbers wanting to attend. A decision was made to build a large chapel at Goodshaw, on what was the main route from Burnley to Manchester. The satellite hamlets and villages were not connected to Goodshaw by road, so worshippers would make their way over the moors by footpaths, the journey being particularly arduous in winter.

Goodshaw Chapel, like other nonconformist places of worship at the time, was constructed as a simple, unornamented building. Unlike the buildings of the Church of England, there was a lack of extensive funds, but the congregation would take a pride in an interior and exterior of sparseness, which set them apart from the established church. The fittings from the original chapel at Lumb, including the bench pews, were carried over Swinshaw Moor to Goodshaw.

The Larks of Dean

Goodshaw Chapel became a focal place for The Larks of Dean. The Sunday services could last a very long time, with some accounts of them carrying on into the early hours of Monday morning. Weekly practice time would eat into hours that should have been spent working, and with many self-employed as handloom weavers, they would have to catch up on work in their own time.

The Larks composed a huge number of psalm and hymn tunes, estimated at somewhere over a thousand. John Nuttall’s two sons, James and Henry, were the most prolific, with Henry producing over a hundred compositions. James wrote 35 pieces, including a setting of the Isaac Watt hymn Salvation! O, the Joyful Sound which, when performed, lasted half an hour. James’s three sons (referred to as John O’th James O’th Parson’s, Jemmy O’th James O’th Parson’s and Dick O’th James O’th Parson’s) were also involved in the group as players and composers.

Richard Hudson’s son, Reuben, was also a plentiful contributor of new music. He held local singing classes as well as having a sideline in giving people legal advice, which led to the nickname “the little lawyer”. His grandson would go on to compose 50 pieces.

Father, Robert, and son, James, Ashworth were a third prolific family. On one occasion, James came across a new piece his father had written. When he asked him what it was called, his father replied “Ca’ it what tha likes”. Such an attitude often resulted in compositions being given unusual names. This irreverence over naming new works was common amongst the Larks, as shall be detailed later in this piece. Once, an old deacon rebuked Robert for practicing a hornpipe tune on his cello in between services. The deacon stated that it was “an idle tune”, to which Robert replied that there were no idle tunes.

A further tale is told of Robert and James practicing late at home one night, on a piece they could not master. They retired to bed where James dreamt a solution. He woke, reached out thinking his violin was nearby, but banged his hand on the wall. He then rose, went and woke his father and persuaded him to get out to bed to resume their efforts. Some versions of the story go on to relate how a passing night time traveller hearing ‘ghostly music’ was startled to see Robert and James, clad only in their night shirts sawing away on their oboe and violin. The tune which they completed in the dead of night they dubbed ‘The Masterpiece’.

Such dedication to hours of practicing seems to have been a hallmark of the Larks. At one group session that had run on past midnight, a young man got up to leave as he had a five mile walk home, and an early start the next morning. An elderly lark, who himself had two ranges of hills to cross before he would reach his own house, remarked that if the young man was always in such a hurry that he would never make a musician, as long as he lived.

Even while at work, the Larks were constantly thinking of creating new pieces. Phrases would be written on a wall, or scratched into a flagstone, wooden board, or even on the back of a spade.

A Change of Minister

After 45 years of being in charge of his congregation, minister John Nuttall died in 1792, aged 76. His plaque in the church states (spelling as in the original):

Dear Friends farewell; my Race is run. I’ve fought the Battles of the Lord. My Foes are slain, my Work is done, And I receive the free Reward. May Love and Peace preside with you, And Reign in all your Works and Ways; And when you bid this World adeu, With me you’ll see your Saviours Face.

The new minister, John Pilling, would see the Goodshaw Chapel enlarged twice during the early 1800s, to cope with the growth of the congregation, swelled by the local thriving textile industry. The gallery was enlarged and the southern front (where the main entrance is today) was extended into the churchyard. Records of the Baptist Building Fund from 1801 show that an appeal raised £95 from the London Baptist churches to pay for building work. In 1809, a school house was constructed adjoining the chapel.

John Pilling died in 1835, aged 76. Whether his passing led to tension in the congregation is not clear, but doctrinal differences were a frequent form of strain within nonconformists. A conflict did occur at Goodshaw, with a manuscript revealing the names of deacons and members “suspended from Communion May 28th 1842”.

In 1860, Goodshaw Chapel was closed due to its lack of space, and a new larger chapel built on the same Burnley road. Services were still held at the old chapel once a year, to commemorate its founding.

Chronicling the Larks

Edwin Waugh, the famous dialect poet, wrote about his meeting with some of the Larks of Dean in his book on the 1862 Cotton Famine of Lancashire. In it, he explained how many people without work during that era were forced into playing for money in the streets. As a way of explaining the preponderance of musical talent during that time, he recounts a story of how while out walking with a friend on the moors he came across a group of the Larks:

“In the twilight of a glorious Sunday evening, in the height of summer, I was roaming over the heathery waste of Swinshaw, toward Dean, in company with a musical friend of mine…when we saw a little crowd of people coming down a moorland slope far away in front of us. As they drew nearer we found that many of them had musical instruments…He inquired where they had been, and they told him they had “bin to bit of a Sing deawn i’th Deighn.” “Well,” said he, “can’t we have a tune here?” “Sure yo con, wi’ o’th plezzur i’th world” replied he who acted as spokesman…They then ranged themselves in a circle around their conductor, and they played and sang several fine pieces of psalmody upon the heather-scented mountain top…Long after we parted from them we could hear their voices, softening in sound as the distance grew, chanting on their way down the echoing glen, and the effect was wonderfully fine.”

Moses Heap, a pupil of Robert Ashworth, is seen as the last of the Larks. Towards the end of his life, he wrote an account of the group. A former mayor of Rawtenstall, Samuel Compston, wrote 13 lengthy articles based on Heap’s account, preserving their memory for posterity. Heap also copied out 255 of the Larks’ songs into a manuscript. This was a huge task and took him 14 years to finish. Completing the work at aged 80, he handed the manuscripts to Rawtentstall Library in 1904. All the Larks’ manuscripts are now held largely in Lancashire County Archive at Preston, with a smaller number in the Whittaker Museum at Rawtenstall. There are many unusual names for the pieces (spellings as the original): Bocking Warp, Flats and Sharps, Flea, Heavenly Church Meeting, Judgement Realised, Lark, Linnet, Lively Sandwidge, Mount Zion, Nabb, Old Crack, Plover, Robin Hood, Solemnity, Ten Commandments, Time in Truth, Scrap Tune, Skylark, Solemnity, Spanking Roger, Whineing Tune and Whirlwind. The Whittaker also contains a cello, fiddle, clarinet and serpent that once belonged to the players.

There is now a modern Larks of Dean Quire, based in Bury. Their website lists their performances since 1994 up until the present day. They sing hymns, psalms, anthem and carols, with an annual performance at Goodshaw Chapel. Their website contains audio recordings of Spanking Roger, Lark, Egypt, and Prodigal Son. To listen to these songs and to read more about the work of the modern Larks, see here.

Preserving Goodshaw Chapel

By 1960, the chapel was still just being used once a year, but the fabric had become unsafe. In 1975, it was recognised as a rare surviving early nonconformist place of worship, with many of its original internal features in excellent condition. The following year, it was transferred by the Trustees by deed of gift to the Department of the Environment. In 1984, a full restoration took place, with it opening to the public the following year, and it is now managed by English Heritage.

Visitors to the chapel can see the evidence of the importance of the music of the Larks. While most non-conformist chapels would have their musicians positioned in the west gallery, at Goodshaw this is not the case. The singers’ pew and orchestral space is directly in front of the minister’s pulpit. Box pews are arranged on three sides on both the upper and lower floors, facing this central performance place. There are other intriguing features within the building. A portion of the pews under one of the galleries are furnished with hinges and hooks, so they could be lifted to allow burials underneath. The upper galleries contain fragments of turquoise paint, evidence of an earlier colour scheme.

As part of the British Textile Biennial 2023, a film was commissioned and displayed at the chapel. This was Larksong, which featured images of the countryside surrounding Goodshaw and an original soundtrack. Poet Emily Oldfield wrote a specially created piece entitled The Pew Watches, The Hand Sows, written from the perspective of a chapel pew, witnessing the changes over the centuries. In the upper gallery, a series of calico prints of wild plants linked to textile production was displayed.

For those that missed this excellent event, a live performance of Larksong, which contains Emily’s poem, can be seen for free on the Vimeo website here. (Note, you can either download this to view on your computer by clicking the download button, or stream it. If you wish to stream it, then you need to set up a free Vimeo account). Emily’s poem is contained in a booklet which can be purchased here. To see some of the images displayed at the chapel during the British Textile Biennial 2023 and for more information on the artists and musicians behind the event, see Nick Jordan’s website here.

Site visited by A. and S. Bowden 2023

Access

Goodshaw Chapel does not have regular opening times, but the key can be obtained by contacting the key holder here. See the English Heritage website below for further details.

Even if access to the interior cannot be gained, it is still worth seeing the outside of the chapel and its fascinating graveyard.

The chapel is on Goodshaw Lane. This is quite narrow at both ends, so the visitor is recommended to approach via Goodshaw Avenue, which is wider. On street parking on Goodshaw Avenue.

Nearby

References

Goodshaw Chapel

On site interpretation at Goodshaw Chapel

english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/goodshaw-chapel/

rossendale-fhhs.org.uk/files/rawtenstall_churches/church_006.html

rodingmusic.co.uk/what-is-west-gallery-music/

Larks of Dean

Aspects of Musicality in the industrial regions of Lancashire and Yorkshire between 1835 and 1914 with

reference to its educational, sociological and religious basis, Christopher Howard Seymour (1986) Durham Thesis, Durham University. Available free online as a pdf from Durham E-Thesis online.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larks_of_Dean

springhillhistory.org.uk/blog-3/files/f8a3bb5692ddf9323e9d8454e206c330-190.html

minorvictorianwriters.org.uk/waugh/c_sketches_2d.htm

thewhitaker.org/collections/social-history/larks-of-dene-music-manuscripts-2/

fulwoodmethodist.org.uk/fmcmag/summer%202007/larks/larks_of_dean_quire.htm

sites.google.com/site/larksofdean/rossendale-musicians

archive.org/details/MyLifeAndTimesByMosesHeapOfRossendale18241913f

The modern Larks of Dean Quire

sites.google.com/site/larksofdean/Home

Larksong- British Textile Biennial 2023

Larksong: The essence of the same Emily Oldfield (2023). The booklet is available here

nickjordan.info/larksong.html

vimeo.com/879725616

britishtextilebiennial.co.uk/programme/nick-jordan-and-jacob-cartwright-larksong/

Comments are closed.