In 1864, a new house to be known as ‘Ashleigh’ was to be constructed in the grounds of White Hall at Darwen. A large mound existed on the plot, into which trees had been planted in 1820. When these were removed in preparation for levelling the site and the digging of the house foundations, it was discovered that the mound was a Bronze Age barrow.

It was perhaps always suspected by local people that this was an ancient site. Historian John Dixon writes that the place was believed to be the haunt of ‘boggarts’- a catch-all term that could mean either a goblin-like creature, or a ghost. He states that children would remove their clogs and shoes when walking past at night, so not to disturb any supernatural residents.

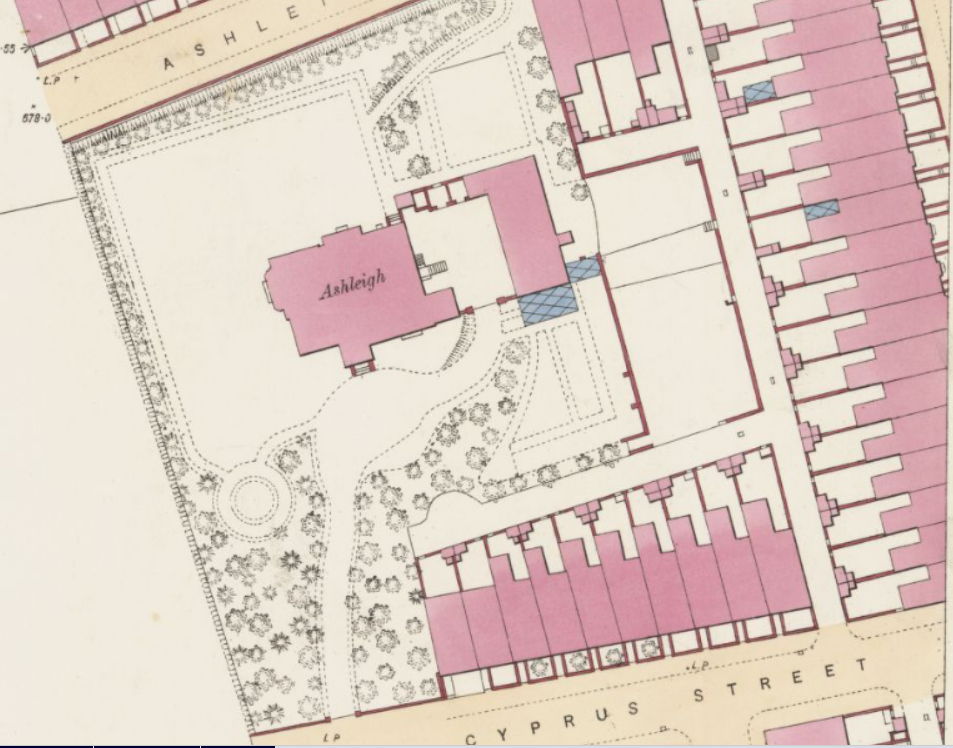

On visiting the place today, it is perhaps hard to imagine how it would have appeared in the Bronze Age. While prehistoric moorland sites such as Winter Hill and Noon Hill retain their remote feel, Ashleigh Barrow is now surrounded by terraced housing. The spot would have originally been a commanding one, and the fact that this is on the slope of a steep hill is telling. Bronze Age burials were often not built on the summit of a hill, but on a ridge or skyline that could be viewed from below. Ashleigh Barrow was on a plateau that overlooked the Darwen valley.

From measurements taken at the time of destruction, the circular mound was some 90 feet in diameter. It was of variable height, 10-12 feet on its eastern side, but only 2-3 feet on the west. It had clearly come to the attention of antiquarian ‘treasure seekers’ before it was levelled, as the centre had a depression measuring 6 feet in diameter where it had been dug.

At the time of its destruction in 1864, ten cremation burials were discovered, nine of which had been contained in burial urns. The pots, classed as ‘collared urns’, were only at most a couple of feet below ground and most were very badly damaged. However, two were largely intact and were later designated as Urns A and B. Eight of the burials were found within a cluster, measuring some 21 feet by 14 feet. All but one of the pots were buried upright, and each of these had a rough flat stone on top of them. Surrounding each urn were small stones, carefully piled up around them.

Both Urn A and B had a small cup inside them (the significance of which will be discussed below). A bronze dagger was also recovered from the site, along with smaller bronze metal workings. The pots were put on display in Darwen Library, where they have remained for decades right up to the present day. They are housed in a glass case in the reference section so that the public can inspect them at close quarters.

Late Twentieth Century Developments

After it was used as a residence, Ashleigh House later became a school. In 1986 it was demolished, but on further excavation nothing more was discovered in the way of archaeological finds. Four years later, the Ashleigh Conservation Group was set up, and with the help of Blackburn Groundwork Trust it began to improve what had become a neglected place. The Ashleigh group decided to commemorate the Bronze Age barrow by creating a banked circle, close to where the original mound stood. Although it is not a replica of the original mound, it is a distinctive feature that can be visited by the public and is sizable enough to be visible in the satellite photographs of Google Earth. At one point in the circle is a small entrance way, which reveals the drystone walling technique that was used to create the feature, which was then turfed over. Surrounding the circle, a small park area was set up.

In 2011, the Friends of Ashleigh Barrow group was actively maintaining the small park, keeping the grass cut back and the paths clear, and even commissioning an ecological survey. Today, local volunteers still work on keeping the paths functional through the area, and take part in litter picking.

An Analysis of the Finds

Dating analysis of the charcoal from one urn was 1940-1740 BC, and from a second urn 1980-1770 BC. From the same second urn, the cremated bone was dated from 1890-1730 BC. This range of results puts the burials in the early Bronze Age period.

Urn A was the best preserved pot, and has been described as “nearly perfect”. Standing at 12 inches high, it was decorated by indented dots which would have been formed by pushing a stick into the wet clay, before the urn was fired. Inside, it was full of cremated bone, on top of which rested a small funerary cup.

Urn B has a cross hatched pattern on its large rim which extends onto part of the bowl section beneath. On its middle part and inner collar a twisted cord was pressed into the clay to produce an imprint (which can be just about made out on the inner collar by the faded label in the picture below). This also had a small funerary cup placed within it.

Although only two intact urns were described at the time of discovery, today in Darwen library there is a third one, (which will be designated Urn C for this piece). It was presumably pieced together meticulously in the intervening years. This has a cross hatch pattern on its large rim, but a contrasting herring bone pattern beneath.

The small funerary cups that were found inside Urns A and B pose a question – what were they for? Funerary cups have a variety of names in the historical literature, variously referred to as incense cups (as some of the first found originals had holes cut into them, as if to release an aromatic vapour), pygmy vessels (because of their diminutive size) or accessory vessels (because they usually accompanied a burial urn). These types of cups are very variable in their decoration, some having elaborate patterns, but many others, like the Ashleigh ones, no decoration at all.

Academic archaeologists still do not know what the small cups were used for, despite efforts to categorise them and analyse their insides for residue. As suggested above, one of the first ideas was that they were used to burn incense but a large scale survey of the cups in Britain has failed to find any evidence of what they might have held. Another suggestion was that they were for deceased infants, but this has since been disproved as there are child cremation burials that contain full size urns. More recent suggestions are that they were used for carrying tinder and kindling for the funerary pyre, or to burn hallucinogenic preparations.

What is now clear from the research literature is that the large collared urns and small cups were made at different times and in different ways. The urns that would contain the cremated remains were carefully made and fired in a kiln. In contrast, the small cups were put on the funeral pyre as unfired vessels. The evidence from this comes from their burn marks and from ‘spalling’- pieces of the clay breaking away from the surface of the cup as it is exposed to sudden intense heat.

Along with the pots were found bronze artefacts. Most of these were very small and heavily corroded, so their use could not be ascertained. The most significant metalwork find was a bronze dagger (or knife). This was found in a pot (neither Urn A or B) and measures 7 and a half inches long. Dr David Barrowclough in his seminal book Prehistoric Lancashire discusses the significance of daggers in some detail. He states that these were the most common grave good placed within burials in Lancashire. Barrowclough then speculates as to why this might be. A knife is a very useful piece of equipment, so perhaps it was thought it would continue to be of use to the owner in the afterlife. He also gives another intriguing reason: that symbolically the knife represents a severance of the living from the dead. He states this to be the belief of the Iban people of Borneo. At first glance, it might seem like a stretch to compare the beliefs of the Bronze Age deceased of Northern Britain to the animistic beliefs of a people on the other side of the world, but there are only so many ways that humans construct and understand spiritual beliefs about the dead. The knife is not on display, but one from Pendleton is on show in Clitheroe Castle Museum (see our page with a photograph of it here).

A further symbolic act appears to be the topping of each of the upright pots with a stone slab. This might be a way of ‘containing’ the dead, so that they do not return to haunt or interfere with the living. The one upside-down pot did not have such a cap, the ground itself presumably providing an adequate seal. Barrowclough’s work on Bronze Age pots in Lancashire sites shows that there are equal numbers of upright and inverted pots. Why some were put in upright and others upside down is an intriguing question. It may represent a change of belief about the afterlife over time, or something to do with the person or persons interred in the urns.

While some people feel that we will never understand the beliefs of people from so long ago, there is reason to believe that one day we will. By comparing finds from archaeological sites regionally, nationally and then through Europe, a picture of practices is being built up. By then incorporating anthropological findings from modern tribes that take part in nature and ancestral worship, together with shamanic practices, perhaps one day we will know just what was going through the minds of the Bronze Age tribes that lived in what would one day become Lancashire.

Site visited by A. and S. Bowden 2024

Access

The reconstructed circle can be seen during daylight hours in Ashleigh Barrow Park. There is on-street parking on Ashleigh Street.

Darwen Library has the three collared urns and two small funerary cups in its reference section. There is free parking on Darwen Market rooftop, just across from the library.

Opening times for the library:

Monday 10 am – 7pm

Tuesday closed

Wednesday 10 am- 5pm

Thursday 1pm-5pm

Friday 10 am – 5pm

Saturday 10 am – 2pm

Nearby

Holker House and Darwen Heritage Centre

Steam Tram Turning Triangle and Twin Waiting Rooms

References

Prehistoric Lancashire, David Barrowclough (2008) History Press. This book is still available new and second hand and is the most comprehensive survey of the county published to date.

Journeys Through Brigantia Volume 11: East Lancashire Pennines John Dixon (2003) Autsteiger Publications

Funerary and Related Cups of the British Bronze Age Claire Cooper, Alex Gibson, Deborah Hallam (2022) Archaeopress Publishing

digventures.com/2018/01/site-diary-why-bronze-age-people-buried-their-dead-with-accessory-cups/

bradscholars.brad.ac.uk/handle/10454/14861?show=full

warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/warwickclassicsnetwork/romancoventry/resources/prehistoricbritain/bronzeage/

National Library of Scotland map website. Darwen – Lancashire LXXVIII.4.4. maps.nls.uk/view/229914459

aldridgepioneers.wordpress.com/2011/09/20/20-september-2011-1502/

Comments are closed.