The Surey Demoniack is an intriguing story of alleged demon possession in Lancashire, from the late 1600s. Our knowledge of the events derives from a lengthy pamphlet that narrated a ‘believer’s view’ of demon possession. It was written by the ministers involved in attempts at exorcism. These men were known as Protestant nonconformists, that is they did not belong to the established Church of England. (Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Methodists and Quakers were all nonconformists.)

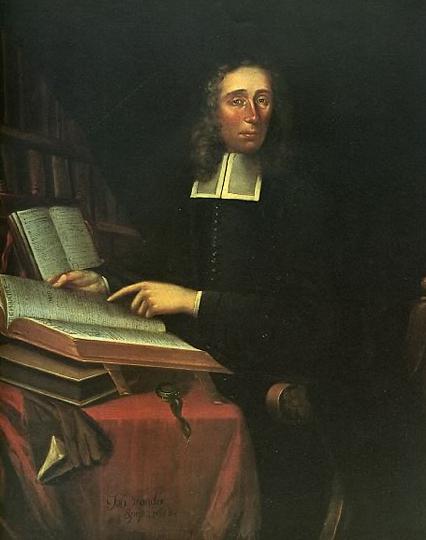

Their publication was entitled The Surey Demoniack or an account of Satan’s strange and dreadful acting, In and about the body of Richard Dugdale of Surey, near Whalley in Lancashire. Six ministers were involved in the case, but the pamphlet appears to have been written by minister Thomas Jolly and trainee minister John Carrington. The publication is the principal source of information of this strange story, but it is at best an unreliable guide, particularly in some of its interpretations as to what actually transpired. Soon after its printing, a long rebuttal was published called The Surey Impostor, written by Church of England clergyman Zach Taylor. He severely questioned the truth of the reported strange events, and personally criticised the ministers involved.

The Surey Demoniac alleged that the subject of the possession, Richard Dugdale (or ‘Dicky’ as he was commonly known), had given voice to a terrible bargain at a rush-bearing festival. This occurred in Whalley on 25th July 1688. Amid the dancing and drinking, Richard declared he would offer himself to the devil, if the devil would make him a good dancer. When he reached home, Richard started fitting and had a burning pain in his side which he later described as if he had been whipped with nettles, or stabbed with needles.

He claimed that while alone at home a series of apparitions appeared before him. The first was a table spread with ‘“dainties” and a voice from beneath it told him to eat his fill. Next a table with fine ornaments appeared, and finally one with “gold and precious things”. Each time a voice encouraged him to take what he desired. He claimed to have resisted all these temptations, and that there were no more apparitions. What did occur subsequently was that he would have frequent fits and outbursts of dancing.

His family took him to see two doctors, Dr Crabtree and Dr Crew, but the authors of The Surey Demoniack claimed that neither seemed able to help. In turn they sought out the help of the nonconformist ministers. Accordingly, on 29th April 1689, Richard was brought to the farmhouse of Thomas Jolly at Wymondhouses, Pendleton, under the shadow of Pendle Hill. Jolly had been a pastor at the church in Altham, but had been removed from that position during the restoration of King Charles II, when nonconformists were no longer tolerated in such posts. Imprisoned many times for his beliefs being at odds with the Church of England, Jolly was a man assured of his own religious convictions and condemning of those that differed.

Jolly believed that Richard’s fits were caused by him being possessed by the devil, in the form of some (as yet unnamed) demon. He tried reading from the Bible and praying in an unsuccessful attempt to cast it out. Undeterred, on 8th May, more of Jolly’s ministerial colleagues met with Richard at a place called the Sparth. After hearing Richard’s story, the ministers started Bible reading and praying.

The ministers began to have regular meetings in which they would fast beforehand, read from the Bible, expound and pray before Richard. Throughout the proceedings Richard would frequently fit, fall in a dead faint, or have to be restrained by strong men holding his arms and legs as he sat in a chair. He would make noises that witnesses said sounded like swine, bears and even watermills.

The meetings mostly took place on roughly a weekly basis at a barn known as ‘The Surey’, which seems to be a place that Richard’s family rented, along with their house, from Sir Edmund Assheton. Sir Edmund was the powerful local landowner and resided in a fine house set amongst the grounds of Whalley Abbey. The five ministers who initially administered the ‘treatment’ were Thomas Jolly, Robert Waddington, Charles Sagar, Thomas Whalley, and Nicholas Kershaw. The local vicar of Whalley, Stephen Gey, was informed of what was to be done, but the Church of England strongly disapproved of exorcisms, believing that they stirred up social unrest as they could easily lead to accusations of witchcraft.

Mr Carrington Arrives

On 16th July, Richard ‘prophesised’ that “One Carrington will this day shake me terribly”. John Carrington was a trainee minister, but would go on to be the star of The Surey Demoniack narrative. When Carrington was first called to prayer by the ministers Jolly and Sagar, Richard raged furiously at him, struggling to attack him and shouting “Oh Carrington, I hate thee mortally, Oh I’ll be revenged on thee”.

On 25th July, the event was moved to a barn at Altham. Such was the crush of the audience a post in the barn was broken down, but fortunately no one was hurt. The following week, back at The Surey, Richard appeared to speak in what the audience believed was Latin and Greek. He also declaimed against the sins of rich people saying “That as maids do sweep away spiders webs, so would their wealth be swept away”.

On the next occasion, Carrington arrived late at the barn and Richard proclaimed “Thou comest too late …, I defie thee, thou art but a weak faith, thou canst not prevail against me, thy faith is but hypocritical …”. The crowd asked Carrington to stay and work on Richard during the night. Carrington agreed to do this. He preached and read from the Bible, sang psalms, prayed over Richard, and questioned him. Richard had three fits and six men were required to hold him in place when he would try to break free.

Richard threatened to take Carrington to hell, shouting “When I get thee to Hell I will make thee my porter to carry damned wretches from one bed of flames to another”. He then named people that had died who Carrington knew, and said they were in hell. Carrington was visibly shaken by this and, trembling, he leant against a chair to prevent his legs giving way. He soon rallied though and continued his ministrations, in total working on Richard from two o’clock in the afternoon until seven o’clock the next morning. The crowd encouraged him to stay on, but when he took a break outside the barn, he found that he had become so hoarse he could hardly speak. The other ministers were sent for and they took turns performing the readings, praying and exhorting.

From the autumn onwards, Richard began to speak more frequently in a ‘demon voice’, and would sometimes be heard arguing to and fro with it. On 3rd September, the demon said it would carry him off to hell in 50 day’s time. Towards the end of the month, the ministers asked him how the demon had entered into him. They asked if he had had an illness that had let the demon in, or had a witch put a curse on him? They also suggested that Catholic priests (which they called ‘Religious Wizards’) could have put it in him so that they could earn the glory of casting it out. Richard was reluctant to answer, but eventually said it was because of “a wish and a vow”. His demon voice then said that he wanted to be a good dancer and would give himself to the devil if he was made one. Richard’s demon voice said he would call out his sister Ischol to attack the ministers. Suddenly a mouse was seen running in the barn, and the crowd called out that it was an imp. The ministers were more interested in debating points of theology and told him that devils did not have genders. Richard again fell down in a fit and cried out for water saying “There is a fiery furnace in me that almost smothers me”.

At the start of October, Carrington was back on his own in the barn. Richard appeared to vomit up a lump of paper, and told Carrington to read it. He then started dancing, leaping high, landing on his knees, then springing up in the air, to land on his feet. Carrington derided his dancing, and compared it to the hopping of a frog, the frisking of a dog and the gesticulations of a monkey. This seemed to put Richard off his capering, and he fell down into a dead fit. On examination of the paper, after it had been unfolded and dried by a fire, the onlookers thought it had Greek writing on it, and perhaps the number 600.

Carrington wanted to work on Richard again the next day. That evening, he spent the night at a local unnamed gentleman’s house, who was sceptical of the whole affair and debated with him into the evening. The next morning, while washing himself, Carrington put his face in the wash basin.

When they were together in the barn, Richard recounted this act, but also accused Carrington of drinking water from the basin. If he had done so, he would have been breaking his fast (as the ministers would not eat or drink before their daily dealings with Richard). Carrington denied doing so, but was visibly shocked and asked Richard which devil had seen him doing this. Richard replied that it was called Melampus. Carrington then began quizzing Richard about the different demons he had mentioned, and at the naming of Beelzebub, Carrington dubbed him the ‘Lord of the Flies’. The onlookers, perhaps not following the debate, started to believe at this point they could see flies flying up Richard’s nose.

Mr Jolly accompanied Carrington the next day and, while he ministered to Richard, Carrington took a break and rested at the nearby river. He had asked a young man to come and get him when he was needed. However, with around a thousand people clustered around the outskirts of the barn, the young man could not get through to rouse Carrington. When Carrington failed to appear, Richard, speaking in his demon voice, declared that Dicky was now his own. Eventually, when Carrington managed to force his way through and came rushing into the barn, Richard responded by raging and hurling from him those people holding on to him.

The following week, Carrington came into possession of a box belonging to Richard. He believed that Richard had a written contract with the devil and sought proof from the papers contained within. The papers were oddly shaped, some had small holes pricked into them, and had been drawn on with a pen. Carrington made much of this discovery but could not make sense of what he was looking at.

When 22nd October dawned, expectation was in the air. This was the day the Richard had prophesised that he would be carried to hell by Satan. However, Richard, again speaking in his demon voice, stated that Carrington, his “tormentor”, had saved him. Two weeks later though, events took a sinister turn. Richard said that Carrington would not be seen after the end of the day. The crowd begged Carrington not to go home that night, fearing for his safety. Richard gave him a large apple, as big as two fists, saying it was a token of his love and respect for all Carrington had done for him. Richard’s mother told him what a fine apple it was, and that he should eat it. Carrington saved it, resolving to eat it on the way home, breaking his fast.

About a mile from the Surey while riding his horse, he began to eat the apple. He suddenly noticed a hole and something seemed to “bubble and flash” at the bottom of it. Further inspection revealed a second hole. Realising the apple had been tampered with, probably maliciously, Carrington did not throw it away fearing someone else might find it and eat it.

That night, he stayed at a friend’s house and the next morning he carried on his journey. He soon became lost and when his horse refused to continue, he abandoned it. He carried on for the rest of the day on foot, late on wading across a river that was barring his way. Once over the other side, he found himself cold and exhausted and lay down as he did not have the strength to go further. It was a bitterly cold, dark and frosty night, and Carrington began to believe he would die. He began praying and thinking deeply, and after much heart-searching he summoned the strength to stand up and continue. He eventually found a house he recognised and was welcomed in. While staying there, he buried the apple and laid a heavy stone on top of it.

A week later, Carrington confronted Richard who said he did not know how the holes got in the apple. The narrative then bizarrely claims that a 14-pound stone, similar to the one that covered the buried apple, had been found on Richard’s body at around the same time that Carrington laid the stone on the apple in his faraway location. No stones of that type were said to be found around the Whalley area, giving the incident a further ‘miraculous’ twist.

By the new year of 1689, pressure was beginning to mount on Richard. The minsters still had their suspicions that a contract existed between him and Satan, or that witches or Catholic priests had had a hand in the possession. Tensions were rising, but the ministers’ methods were still not producing a ‘cure’.

On 24th March, things finally came to an end. Richard had a “terrible fit” and in his demon voice pronounced “Now Dicky I must leave thee, and must afflict thee no more as I have done, I have troubled thee thus long by Obsessions, and also by a Combination, that never shall be discovered as long as the world endures.” Then Richard’s body was “tossed and tortured, strained and stretched as if vomiting, and tho’ nothing was seen, Satan came out of him”.

After this event, the original narrative of The Surey Demoniack stated that Richard had no more troubles. It relates that Richard told Thomas Jolly that he hoped he had been delivered by spiritual means, which he believed would continue to help him and prevent him relapsing. The main narrative from The Surey Demoniack ends on this note. The rest of the publication consists of numerous eyewitness testimonies of those that saw the events, sworn before local Justices of the Peace. This narrative and the eyewitness testimonies would be severely criticised in a publication that came out the very same year.

The Surey Impostor

The Surey Impostor was written by Zachary Taylor, who called himself “one of the King’s Preachers for the County Palatine of Lancaster”, indicating he was a clergyman in the Church of England. He held the office of vicar at Ormskirk and curate at Wigan parish churches. Taylor dedicated his book to the ministers, but with a barb stating, “not that it seeks your patronage, but your reformation”. He then berated them: “Consider the evil you have done in publishing a wild storey for a religious truth… This trade that you have learnt from the papists, was designed to ensnare honest and well meaning, but easy people. …by working on weak people’s fancies, you might win those to your party, by craft and wiles, which you could not by reason and religion”. He then recounts the ‘possession’ story of The Seven in Lancashire, and how one of the ministers involved in that affair was later imprisoned for his dealings with a similar exorcism case in Nottingham. Here he seems to be warning the ministers that this could be their fate too. For the gripping, full story on The Seven, see our page here.

In the Surey Impostor, Taylor proceeded to systematically debunk the supernatural happenings that occurred around Richard Dugdale. He pointed out that much of Richard’s behaviour was odd, but needed no miraculous explanation. For example, The Surey Demoniack related how Richard on one occasion gathered up the rushes on the floor of the barn. He then dealt them out, as if playing cards, while making the unlikely claim that he did not know the rules of cards. He also used the rushes to pretend he was playing bowls, imitating bowlers saying “Sirrah, stand out of the way, or I will knock your brains out” and then added “I never was a bowler; but do not Gentlemen do thus?”. In actual fact, Richard as a gardener mowed the bowling green at Whalley and would in all likelihood have seen bowls being played.

The Surey Demoniack gives a number of occasions when Richard seemed to be able to see things that happened when he was not physically present at a location, what would now be termed as ‘remote viewing’. The time when he seemed to see Carrington washing and drinking water at the gentleman’s house was his most impressive feat of this kind. His other attempts were less amazing. For example, he stated that widow Chew’s maid had come out of her mistress’s house and said out loud “My Dame has gone to the Holy House of God and I will creep to The Surey”. He told a woman she had cheese and bread in her pocket, and another she had a pipe in hers. Taylor believed that Richard had accomplices that would witness trivial events and then relay them to him through the barn wall. He noted that the walls of the barn were raised up about a yard off the ground, with the lower part being made of reeds. He believed that Richard’s accomplices would relay information to him by whispering through this portion. Taylor accuses Richard’s sister of being such an accomplice.

Another common behaviour Richard would display was the vomiting up of small stones, buttons or curtain rings. Taylor asked why he never brought up precious jewels, or gold or silver objects. The implication here is that the ‘apparitions’ were everyday things that were easily found, and then easily ‘produced’. One witness claimed to have found seven stones hidden together in a nest of straw within the Surey barn, presumably to be recovered by Richard during one of his performances.

Since his ‘possession’, it was said that Richard could run on his hands and knees as fast as a man could run on his legs. But Taylor found a witness from Richard’s school days who stated that he did such things while he was a boy. At school, he would often dash quickly on his hands and knees, spring up from this position high in the air, bark and make other unusual animal noises. This was exactly the behaviour that Richard displayed in the barn. Another former schoolmate reported that Richard would say he often met a witch, who he called Sadler’s wife, on his journey to and from school. This again hints at his willingness to fabricate events.

At one point the ministers had convinced themselves that Richard had made a contract with the devil and were keen to find evidence of this. A search of some of his belongings uncovered some papers in a box, with the papers having “unusual designs” and pin holes in them. Carrington made much of these findings but could not decipher them. However, a more down-to-earth explanation was given by Taylor. It transpires that Richard and some of his friends had wanted to learn to draw, and had got together pictures of bears, dogs and wolves in different poses, along with designs from Sir Edmund Assheton’s coat of arms. They put pins in these, penetrating the blank paper they had placed underneath. The pin holes were to be later joined together, in a dot-to-dot fashion, to recreate the pictures.

Taylor also discussed in The Surey Impostor if Richard might have epilepsy. He thought that some of the fits could be genuine, while others were not. He gave the example that Richard would frequently state how many fits he would have in a day. He would then proceed to have exactly that number, and was thereby deliberately faking them so that this number was proved correct.

Taylor’s reasons for the end of the affair

The original narrative of The Surey Demoniack seems to give a rather arbitrary ending, after months of the ministers’ work. Taylor gives a number of other reasons why he believed the ‘possession’ ended. It had been recorded that Sir Edmund Assheton had grown tired of the constant large numbers of people turning up at The Surey to witness the spectacle. The official narrative states that he was concerned with the damage that was being done by the masses to his hedges. This may or may not be the reason for his patience wearing thin, but it may just have been that he was fed up with the spectacle on his lands and the public insubordination Richard showed to him.

On one occasion, Sir Edmund went to The Surey accompanied by his butler and relative Sir Ralph Assheton of Middleton. When Richard saw them, he roared that they had been abusing him in the buttery of Sir Edmund’s house. He raced up to them, but when they gave no ground, he responded by flipping through the barn and running outside. He then headed for the River Calder and ran into it. The crowd followed, and Richard’s parents cried out that he would drown. Richard threatened to drown anyone who came to save him. He stood in the water, crying out “Whilst thou drown me? Whilst thou drown me?” presumably addressing his ‘demon’. The chilliness of the water eventually calmed him down, and he was thrown a rope and pulled out.

Taylor also stated that a medical cure could have been the part of the reason why the fits stopped, believing at least in part that some of them could have a physical cause such as epilepsy. At the instigation of the three most powerful men of the area – Colonel Nowell of Read, Sir Edmund Assheton and the vicar of Whalley, Stephen Gey – Dr Chew prescribed medicine for Richard in March 1690. After taking it, Taylor claimed, the fits stopped. Richard originally had been prescribed medicine by Dr Chew at the outbreak of the whole affair, before he was first brought to Thomas Jolly by his family, but Taylor claimed that he had never taken it. It is very doubtful that medicine from four hundred years ago would produce such a cure if the fits were genuine, so perhaps a further solution can be offered, and this is given by Taylor himself.

The most likely reason for the end of the affair is that the ministers, tired of their methods not working, began to threaten Richard and his family. Taylor stated that after the incident with the suspect apple, Carrington raged that he would have the family prosecuted for witchcraft. While possession was not an offence, witchcraft was, and if convicted it carried a hanging sentence. The Pendle Witches trials had been carried out back in 1612, but there were still active witchcraft prosecutions in England at the time. Three women had been convicted and killed in Bideford in Devon just seven years before. Interestingly, these threats of putting the family on trial for witchcraft are not mentioned in the ministers’ account of The Surey Demoniack, perhaps because they knew that this would reflect badly on them. It is only Taylor, their chief critic, that supplies this detail in his The Surey Impostor.

Taylor also considered at some length what Richard’s motives were for starting the ‘possession’ performances in the first place, and for keeping them going for so long. He stated that he believed that Richard thought he would be able to get money for his antics, but from whom it is not clear. Taylor then produces a conspiracy story: he believed that what he termed “popish priests” were behind the whole affair. He claimed that, while working for Sir Edmund, Richard befriended a chambermaid at his hall. Through her, he became known to Catholic priests. A priest would come to Sir Edmund’s house as, although he was Protestant, his wife was a staunch Catholic and would take mass there. Taylor implied that the priests had persuaded Richard to fake possession, and then would “cure him”, to bring “glory” to their cause and recruit people to their version of Christianity.

After this, Richard stopped working at Sir Edmund’s house and became employed at Westby Hall near Gisburn. He had not been there more than two or three months when he ‘”begins to act the Demoniack“. Richard then returned to live at the family home at The Surey, and the narrative, as described in the above account, began to unfold.

Taylor claimed that when the Catholic priests came to make their move and promote Richard as the victim of possession, the “Revolution” happened, and they withdrew from their plan. The Revolution was the so-called Glorious Revolution, when Protestant William of Orange took the crown from the Catholic King James. This was a time of repression for Catholics, and Taylor implied that because of these political events the priests were keeping a low profile.

Taylor next explained that, once Richard’s possession started, into the gap vacated by the Catholic priests stepped the nonconformist ministers to enact their own exorcism solution. At one point, Taylor claimed the Catholic priests sent a “paper” to be read over Richard by the ministers that would “cure” him. This was presumably a prayer, but the ministers did not use it, being as hostile towards Catholics as the Church of England was towards them.

Publication

The nonconformist ministers printed The Surey Demoniack in 1697, seven years after the events took place. Taylor stated the ministers had waited several years so that Stephen Gey (the vicar of Whalley), Sir Edmund Assheton and Colonel Nowell “were all in their graves”, implying that these local upstanding worthies were no longer present to dispute the validity of the information contained within the publication. It is not clear that this is a fair accusation, as it may have taken the ministers some time to write their long account, and then to find a publisher.

Initially, a Reverend Baxter wanted to add The Surey Demoniack narrative to his book, The World of Spirits evinced by Apparitions, Witchcraft etc, but he died before the text was sent to him. However, Reverend London Divine then offered to print it as an appendix to Increase Mather’s book A Further Account of the Trials of New England Witches. Witchcraft accusations had recently come to a head in America with the Salem Witch trials, and The Surey Demoniack would reach a large audience who had presumably already heard of this notorious case. Increase Mather was the most important cleric in New England, and his book recounted the wild and sensational claims of the accusers. Thomas Jolly had been in correspondence with Increase Mather for some time, and they likely shared similar beliefs on supernatural matters – that both witchcraft and possession had similar manifestations and that, in their eyes, one may cause the other.

The manuscript was taken to London to be put into the edition of Mather’s book. On 16th September 1695, at about seven in the evening, one of the authors was out walking in King Street in the Cheapside district. By the Bell and Dragon, an apothecary shop, a dozen men suddenly “clasped about him”. He struggled and called for help, but they made off with what was then the only fully up-to-date proof of the manuscript. This led to a delay in the printing, and so it was not inserted into Increase Mather’s book. The Surey Demoniack was finally printed in 1697 as a publication in its own right.

That same year, Zachary Taylor printed his rebuttal The Surey Imposter, attempting to demolish not only the main narrative but also the many signed and sworn testimonies of eyewitnesses before local Justices of the Peace that were included at the end of the original publication. In this, he did everything he could to discredit any ‘supernatural’ happenings, and severely criticised the methods the ministers used in their treatment of Richard and their theological beliefs.

The following year, Thomas Jolly published a counterblast in A Vindication of the Surey Demoniack as No Imposter, taking issue with many of the claims that Taylor had made on a point-by-point basis. Not wishing to leave the matter, Taylor then published a further rebuttal. This was met with a broadside that attacked Taylor personally, called The Lancashire Levite Rebuk’d. Although this was published anonymously, it was very probably the work of John Carrington. Taylor would not let the matter lie, and published Popery, Superstition, Ignorance, and Knavery confess’d and fully proved in 1699. The conflict may have continued to rumble on in this battle of the pamphlets were it not for the death of all three, in fairly quick succession. John Carrington passed away in 1701 and Thomas Jolly in 1703. Jolly was buried at the church at Altham from which he had been expelled so many years before. Zachary Taylor died two years later. This marked the end of the turbulent period of obsession over witches and demons in Lancashire – there were no more ‘witch trials’ or ‘demonic possessions’ in the county that history records.

Religious Rivalry and the Severe Consequences of Belief

Three distinct Christian groups – the nonconformist Protestants, the Protestant Church of England and the Roman Catholics – were vying for power during the late Stuart era. There was little love lost between them, and their fates were bound up with the politics of the day. The nonconformists had the upper hand during Oliver Cromwell’s rule, but lost their predominance when King Charles II returned to the throne. He had stated he would give religious freedom to the country, but instead reinstalled the Church of England as the official state religion and suppressed the nonconformists. Charles then converted to Catholicism on his deathbed. His brother and heir, the Catholic James II, promoted people of that faith to high positions within the country. Eager to stop a return to Catholicism, Protestant Prince William of Orange was ‘invited’ to take the crown by a group of powerful Protestants. William’s armies fought and beat the army of James, enabling William to become king and rule jointly with his wife Mary (James’ daughter). All these changes took place within just a forty year period and would have been the turbulent backdrop for ordinary people’s lives and even more so affecting the fate of ministers, vicars and priests.

The story narrated in The Surey Demoniac is a long and, at times, tortuous one. It shows that although there was widespread belief in demon possession in the Stuart Age Lancashire, there was much scepticism too. The stance taken was determined by the type of Christianity believed in. The Catholics were very much believers in possession, as were the Protestant nonconformists as evidenced by the ministers in the narrative. The Church of England, as the established church of the country, had a long-maintained scepticism of such things. They believed that demon possession was a thing that had happened in the Bible, but not in the present day. Church of England vicars knew that such events could lead to wilder and wilder accusations, for when there were suspicions of demon possession, accusations of witchcraft were not far behind. This could lead to many members of a community being falsely accused and, after being put on trial, killed. The witch panic that gripped Salem in America just two years after Richard was undergoing ‘exorcism’ was due to the beliefs of nonconformist Protestant Puritans. The resultant witch trials there ended with the deaths of twenty-five innocent people.

Both original documents of The Surey Demoniack and The Surey Impostor published in 1697 make for fascinating study with much more detail than this account can cover. If any reader wishes to look further into these texts, a link is provided below where they can be downloaded and read for free.

Sites visited by A. and S. Bowden 2024

Access

It is not clear exactly where The Surey once stood in Whalley district. It may have been near Sir Edmund Assheton’s house at Whalley Abbey, as he owned the barn and house at The Surey which was rented by Richard Dugdale’s family.

Sir Edmund Assheton’s fine house can still be seen within the ruins of Whalley Abbey. The abbey is open every day to the public for a small entrance fee. Except for the entrance hall (which has a selection of guide leaflets) and a small chapel room, the house is not open to the public as it is a retreat centre for the Church of England. However, visitors are encouraged to walk around the outside of the building and there is an interpretation board that explains its long history through its various architectural stages. The Cafe Autisan in the abbey grounds serves refreshments.

The River Calder can be seen from Whalley Bridge.

Sparth Manor is on Sparth Road, Clayton-le-Moors and is now a private house.

Altham Church is open to the public on certain days in the summer months, including guided tours, see here.

The village of Pendleton nestles beneath Pendle Hill. It is not clear where Wymondhouses, Thomas Jolly’s farmhouse, was. Pendleton has its own intriguing but unrelated history of being the site of Bronze Age burials. See our page on it here

Nearby

References

The Surey Demoniack: or an account of Satan’s strange and dreadful actings, in and about the body of Richard Dugdale of Surey, near Whalley in Lancashire. Thomas Jolly (or Jollie) (1697). For the full text see here

The Surey Impostor: Being an answer to a late fanatical pamphlet entitled the Surey Demoniack, Zachary Taylor (1697). For the full text see here

A Vindication of the Surey Demoniack as no Impostor: Or, a Reply to a certain pamphlet publish’d by Mr Zach. Taylor, called The Surey Impostor, Thomas Jolly (or Jollie) (1698). For the full text see here

Witchcraft, Possession and Confessional Tension in Early Modern Lancashire, University of Liverpool PhD thesis, Deborah Lea (2011). Available online as a pdf document.

The Witches: Salem, 1692 Sarah Schiff (2015) Little, Brown. A superb book, chronicling the full history of the accusations and aftermath at Salem.

en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Dugdale,_Richard

Comments are closed.