Lord Strange’s Men was the acting troupe of Ferdinando Stanley, heir to the Earl of Derby, the most powerful noble in Tudor Lancashire. During his patronage, the Men would become embroiled in blasphemy allegations, the fallout from a treasonous plot against the queen, and face losing their livelihoods after his suspected poisoning. History remembers them for having performed William Shakespeare’s first plays, and for the bard joining them in their next incarnation, as both actor and playwright.

In Tudor times, the Stanleys were the foremost noble family in north-west England, owning huge amounts of land in Lancashire, Cheshire, North Wales and the Isle of Man. The head of the family, the Earl of Derby, was entrusted with many of the most powerful civic positions in the region. (The Derby in his title is obviously not the midland town of Derby, but the then administrative region of West Derby, the west Lancashire and Liverpool area of today). The Stanleys had the largest household in England of around 150 people, twice the size of other nobles. In England, only Queen Elizabeth I had a larger court. Both the earl and his sons Ferdinando and William saw themselves as patrons of the arts. To this end, Ferdinando Stanley assembled his own group of actors.

The possession of performing troupes by a noble family was a show of status, and a form of soft power. They would visit houses of other gentry, and perhaps even end up at the royal court, performing for Queen Elizabeth. The group was called Lord Strange’s Men, after Ferdinando’s title of Lord Strange.

In September 1588, with the death of the Stanley family’s close friend, the Earl of Leicester, Ferdinando sought to recruit some of his former players. The actors were not free to set up and run their own troupe, as sixteen years earlier an Act of Parliament had been passed that forbade any group without a noble patron from performing. Without patronage, the troupes were seen as ‘masterless men’ and the legislation compared such people to “rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars”. Acting groups at this time were self-governing, and consisted of ‘sharers’. This meant that each actor was a ‘sharing player’, having a share of any profits their performances produced, and likewise the losses.

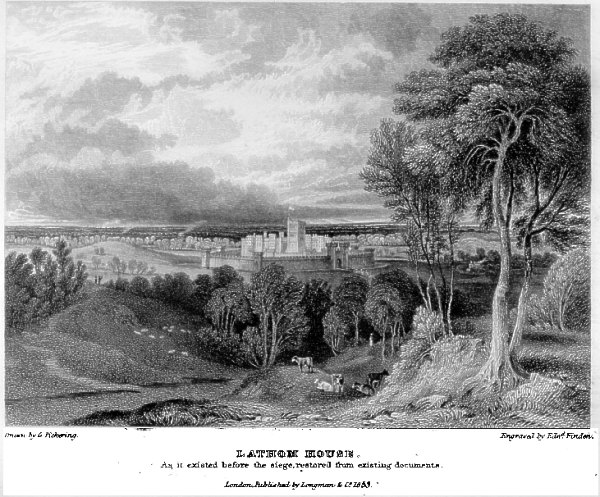

Initially, the group performed at the grand Stanley homes at Lathom and Knowsley during the Christmas period. In January 1589, Ferdinando was summoned to serve in parliament and the actors followed him to London. The first record of Lord Strange’s Men in the capital was at the Cross Keys Inn. This was one of four inns where plays were regularly held. The performances were conducted in large rectangular courtyards, with the audience standing on the ground before the stage, or watching from surrounding balconies.

The troupe’s start in London was less than auspicious. At the time, the capital was gripped by one of the many religious pamphlet wars, where Christians writers would pour scorn on other Christians from opposing denominations, and also challenge the government. This one, known as ‘Martin Marprelate’ (a pseudonym of a puritan writer), consisted of a series of pamphlets mocking the Archbishop of Canterbury. The pamphleteer criticised his crackdown on Presbyterians, and his ability to censor publishers.

Acting companies had been warned by Queen Elizabeth’s government not to allude to the controversy in any of their plays, but Lord Strange’s Men ignored this. On 5th November, they played in defiance of a Mayoral Order, leading to some of the troupe being arrested and flung into gaol for the night. Just six days later, the Privy Council wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury suggesting ways to prevent actors from referencing “in their plays certain matters of Divinity and of the State unfit to be suffered”. Lord Strange’s Men were ordered to surrender their playbooks so that any offending material could be censored.

They returned to Lathom for Christmas, staying in Lancashire until February. The Stanley’s steward, Sir William Farington of Worden Hall in Leyland, kept meticulous notebooks in his role of managing the Stanley’s estate. He was tasked with paying any actors who put on plays for the family, and from his accounts it is clear that they performed for the family on at least four occasions during that period.

In November of the following year, Ferdinando appeared at the Accession Day Tilt, an annual celebration where the aristocracy would joust in front of Queen Elizabeth. The tournament was a throw back to Medieval times, but the lances were designed to shatter easily, and so not cause intentional damage. Afterwards, the participants would address the queen and her ladies in waiting, speaking in an attempt to make them laugh. It is likely that Ferdinando impressed that day and, with his star rising. his acting troupe were asked to perform at royal court for the first time. They did two performances, one in December 1590 and the other the following February.

Records from the time list the names of the sharing actors, giving a clear snapshot of who was a member of the group. The men that formed the core part of Lord Strange’s Men were John Heminges, Augustine Phillips, William Kempe, Thomas Pope, George Bryan and Henry Condell. In May 1591, Edward Alleyn, the leading actor of the day, left his own troupe of the Lord Admiral’s Men to join Lord Strange’s Men. History remembers him for his roles in Christopher Marlowe’s plays Dr Faustus and Tamburlaine the Great. Perhaps because of the addition of Alleyn, Lord Strange’s Men became the premier acting group in the country, and appeared six times at the royal court in the Christmas to February period that followed.

The Rose Theatre Residence and William Shakespeare

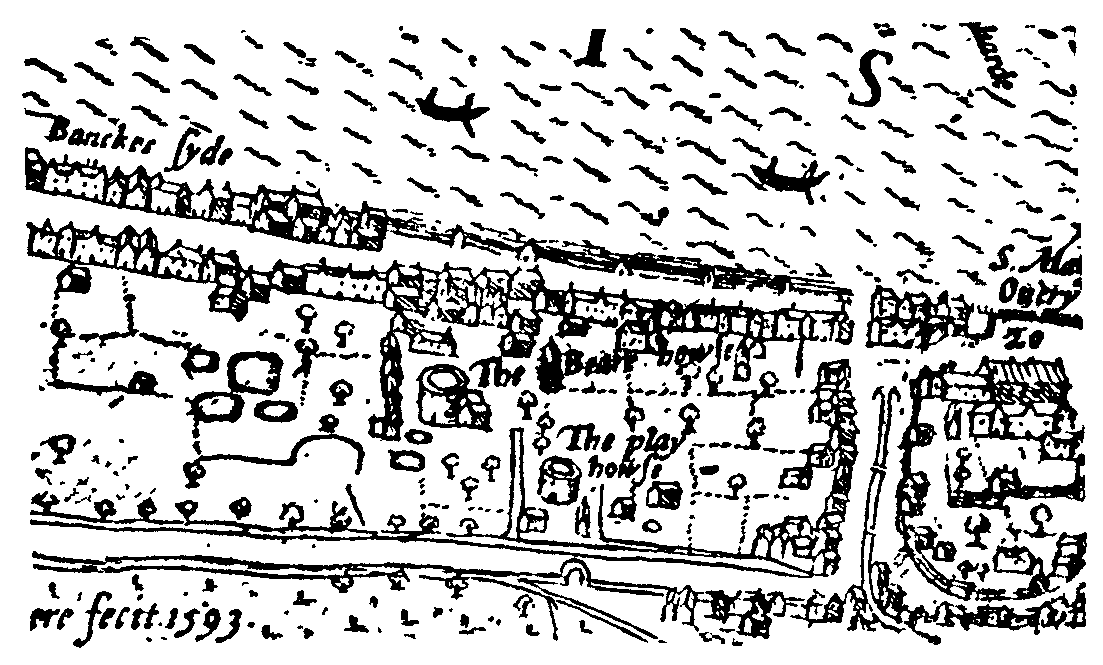

On February 19th 1592, Lord Strange’s Men started an extended season at the Rose Theatre. This was the first long-term residence of any group in a theatre in London. In all they performed 24 different plays, and gave 105 performances between February and the end of June. Most notably, they premiered Henry VI (part 1) at the Rose, Shakespeare’s first published play. It would become the most popular play in their repertoire.

The season finished in the summer, and William Shakespeare was mentioned in print for the first time, but it was not a favourable review. He was described as “an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that his tiger’s heart has wrapped in a players hide”. At this time, Shakespeare was writing the second and third parts to Henry VI, all three parts being separate full-length plays.

Lord Strange’s Men’s residence at the Rose was curtailed for two reasons. The first was that the Apprentice Riot in June had made the authorities nervous of further disturbances. The apprentices had met up in a large group, the pretence being that they were going to see a play. Their actual intent was to carry out disorder. The Privy Council passed a motion to ban all plays in London until Michaelmas (late September), to prevent the apprentices from using the ruse again.

The second reason for Lord Strange’s Men not returning to the Rose was much more serious. In mid-August, London had the worst outbreak of plague to occur in 30 years. This kept Lord Strange’s Men out of the Rose until December. To continue to earn money, they were forced to go on tour. Initially, they visited Sussex and Kent, playing in town halls and guild halls. They then moved on to the south-west, visiting Bristol.

Touring proved difficult for them, and they wrote to complain that “our company is great, and thereby our charge intolerable, in travelling the country, and the continuance thereof, will be a means to bring us to division and separation”. Touring was not easy for any group, and the pressure to make a profit in order to continue to exist was large. Even on tour, the troupe would also have to bring with them a number of hired men for the smaller parts, which further added to expense. One rival troupe had been reduced to selling their clothes to finance their return home.

With the plague subsiding in the winter, Lord Strange’s Men returned to the Rose Theatre for their second residence, beginning on 29th December. This time it was a shorter stay, only lasting until the 1st February the following year. Two new plays were added to their already large roster, and they once again performed Henry VI (part 1). Records show that their lead actor, Edward Alleyn, took on twenty-nine major roles, many of which were hundreds of lines long. The other principal actors, John Hemminges, Augustine Phillips, William Kempe, Thomas Pope, George Bryan and Henry Condell would each perform around sixty-five characters. Life as a sharer clearly involved prodigious amounts of line memorisation.

After this second residence, the Privy Council granted them the right to travel and perform outside London. This time, their tour took them to Chelmsford, Faversham, Bristol, Bath, Shrewsbury and Chester. As they reached the north, it is more than likely they would have come to Lathom and Knowsley to perform at both Ferdinando Stanley’s household, and for his father, the earl. After this, they travelled on to York, before turning south to Leicester and Coventry. Their touring was to come to an abrupt stop though, as huge trouble was brewing for the Stanley family.

A Death and A Plot

In September 1593, the Earl of Derby was dying at New Park, a smaller Stanley residence one mile from Lathom. Ferdinando was in attendance and on the day of his father’s death on 25th September, a visitor came calling. This was Richard Hesketh, an exiled Lancashire gentleman. Hesketh had been sent by dissident Catholics living abroad to sound out Ferdinando over his willingness to take up a claim to the English throne.

King Henry VIII’s will had stated the line of succession that was to follow him for the English throne. His children took precedent: first his son King Edward (now deceased), next his daughter Queen Mary (also deceased) and then the current queen, his daughter Elizabeth. If she had no children, which she did not, then the crown would pass to King Henry’s younger sister, Mary, and her descendants. He excluded his older sister, Margaret, because she had married into the Stuarts, the kings of Scotland. Henry did not want Scottish kings to rule England. If his will was to be honoured, then Ferdinando, the great-grandson of Mary, was next in line for the throne of England on the death of Queen Elizabeth. However, it was up to the queen herself to name her successor, and she had not made any indication that it would be Ferdinando.

Ferdinando did not meet Hesketh on the day of his father’s death, but spoke with him two days later at New Park. Hesketh delivered to him a letter from the Catholic exiles. At Ferdinando’s request, they had a second meeting at Brewerton Green on 2nd October. The next day, they rode together to London. Once in the capital, Ferdinando went to consult his mother, who lived apart from his father as they were estranged.

Ferdinando subsequently went to inform the government authorities of the plot, and gained an audience with the queen on 10th October. This act should have been enough to show he was loyal to her, but it was not seen that way. Unfortunately, Lord Burghley, the queen’s intelligence gatherer on spies and dissidents, did not trust the Stanley family at all. Fourteen years previously, Ferdinando’s mother had been accused of using sorcery and astrology to discover how long the queen would live. Such means were deemed illegal and orders had been given to imprison her in the Tower of London. This was reduced to a form of house arrest. She never recovered her reputation at court, despite pleading her innocence. Her physician who had allegedly carried out the divination had been executed.

At the time of the Spanish Armada, five years before, Ferdinando’s father had been involved in negotiations to stop the fleet from setting forth to invade England. Ferdinando himself was in charge of the defence of Lancashire and Cheshire at the time of the threatened attack. Despite this, Lord Burghley had not trusted them and believed they were involved in a plot to allow 10,000 Spanish troops to land in the north-west, a wild rumour that had no credible evidence behind it. The Stanleys were a Catholic family (though probably not devout) at a time when the official religion of England was Protestant, and the major players in Elizabeth’s government would all adhere to that faith. The fact that the Stanleys had traditionally been Catholics was enough for Lord Burghley to doubt their loyalty to the queen and government, and perhaps believe they would side with Catholic Spain when the Spanish Armada came. Where Ferdinando’s actual religious leanings lay was open to speculation. One contemporary commenting on his faith said “some do think him to be of all three religions (i.e. Protestant, Puritan and Catholic), and others of none.”

Lord Burghley’s intelligence on the exiled Catholic community abroad was more accurate though. He had a number of separate credible reports that ex-patriot Catholics were looking to install Ferdinando as king after Elizabeth died. Agents had been sent to England to gather Catholic support for Ferdinando as a claimant to the throne, without Ferdinando’s knowledge. Cardinal Allen of Rome had openly discussed his suitability. Allen, originally from Poulton-le-Fylde in Lancashire, was the founder of the English College both at Douai and Rome. Priests were trained at these institutions and then sent clandestinely to England to perform the religious mass service in secret for Catholic families. This was an illegal activity during the reign of Elizabeth, and any Catholic priest caught could face execution. Cardinal Allen had also advised on the Spanish on their Armada invasion, and had recommended to Pope Pius V that Elizabeth should be deposed.

The irony in all these suspicions is that the Stanley family were loyal to Elizabeth, and to her own judgement in appointing her successor. It does not appear that Ferdinando had any designs on the throne, at any time. The meetings with Robert Hesketh were seen as Ferdinando participating in the plot, and dealt a severe blow to his political ambitions to take on his father’s duties as the new Earl of Derby. Not only distrusted by Lord Burghley, he was now hated by some Catholics at home for what they saw as his betrayal in surrendering Hesketh, who had subsequently been executed.

Ferdinando retreated back to Lancashire and remained there for the autumn and winter. His worst fears were confirmed when powerful civic positions that had been held by his father were not granted him, but given to others. His wife stated that he would not go back to London as he expected that if he did, he would be “crossed in court: and crossed in his country”. In December, Ferdinando became embroiled in a heated dispute with the Earl of Essex. Essex had given sanctuary to some of Ferdinando’s servants who had left under a cloud, angry with him over the execution of Hesketh. Ferdinando demanded that either the servants were sent back to him, or that they be dismissed. The earl refused, probably to further torment Ferdinando. Essex was a hugely ambitious man, and as shall be seen, a ruthless player in the bid to further his own ambitions.

All this intrigue adversely affected Lord Strange’s Men, whose fate was so closely entwined with his. That winter, they did not return to their residency at the Rose Theatre and, instead, a rival troupe moved in. By January, they were selling their playbooks, and evidence shows that perhaps Ferdinando was no longer their patron. One of their most popular plays, A Knack to Knowe a Knave, had been recently registered to “Ned Allen and his Company“. This implies that they were masterless and probably advertising their own availability for a new patron, using Edward Alleyn’s name as their most famous performer. Their last known performance was at Cauldon Castle in Leicestershire the month before. If they were in dire straits though, for Ferdinando, much worse was to come.

Death

The following Easter, Ferdinando had been hunting for four days at Knowsley, but subsequently on 5th April he became ill, vomiting three times. The next day, he moved to Lathom, but continued to be sick, and sent for doctors. Thinking he may have been poisoned, he took a number of remedies: a bezoar stone (a mass formed in an animal’s intestines from hairs and undigested fibre) and a ‘unicorn’s horn’ (probably powdered bone or fossil). He also administered an enema, and ate chicken broth that contained a laxative made from rhubarb and the manna ash tree.

The doctors did not arrive until the next day, travelling from Chester. In their absence, a local cunning woman had been creating herbal remedies for Ferdinando. The two physicians and two surgeons were professionally suspicious of her, and when they saw her praying (or perhaps mouthing a ‘spell’) over one of her concoctions, they knocked it over and flung her from the room.

Ferdinando continued to vomit and had a yellow jaundiced appearance. The doctors suspected a swollen spleen, possibly due to alcoholism. He began to suffer from severe abdominal pain. The doctors’ remedies were both ghastly and useless, and Ferdinando had the sense to refuse some of them. He would not let the doctors bleed him (a common ‘remedy’ that cured nothing) and also declined their suggestion of swallowing some of his own vomit.

They administered substances to purge him, and applied “oils and plaisters” to his stomach. They also gave him an opiate of diascordium in syrup of lemon, to enable him to sleep. Despite all of this, the frequent vomiting continued. On the seventh day of his illness, he could not pass urine and the insertion of a catheter did nothing to remedy this. In the end, Ferdinando begged the doctors to stop treating him, and allow him to die. They granted his wish, and after twelve days since the beginning of his illness he passed away, at the age of 35.

Afterwards one of his doctors, Dr John Case, stated that it was nothing other than “flat poisoning’” and his attending colleagues concurred. However, when George Carey, Ferdinando’s brother-in-law, headed an enquiry into the death he noted that “the good service he did to her Majesty and the realm, and no private ill desert of his own, shortened his days . . . by villainous poisoning, witchcraft and enchantment, whereof the bottom not yet found”.

It is not clear where the accusation of witchcraft had come from, and why subsequently the idea of poisoning was downplayed. Even the doctors seem to later revise their view, stating that Ferdinando had been bewitched and offering the evidence that his vomiting and hiccupping was eased when the cunning woman became “troubled in the same manner“. This reflected a common belief that a cunning person could transfer a bewitchment from a patient to themselves. They were not accusing the cunning woman of bewitchment, but of easing it.

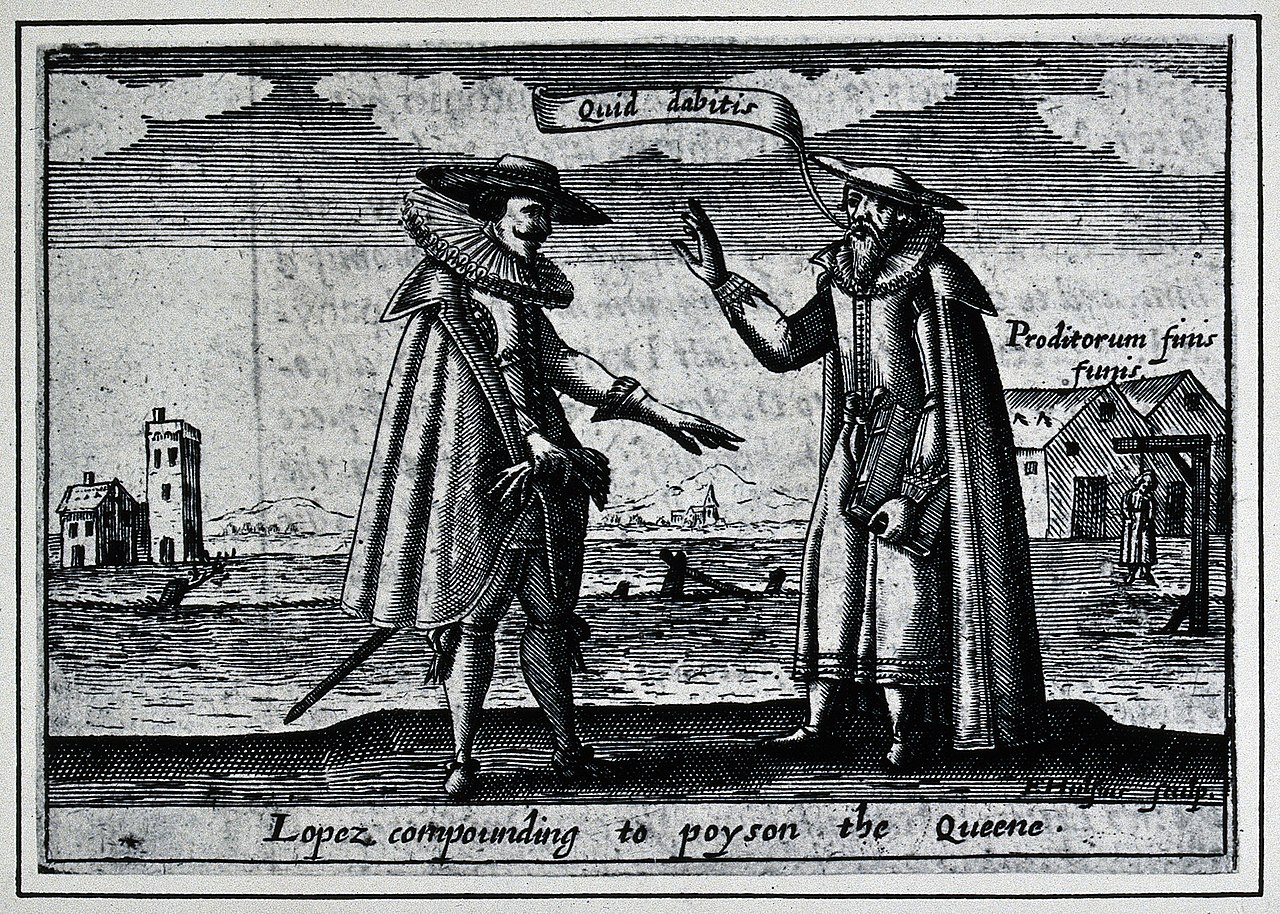

A strong possibility for the shift to a witchcraft diagnosis may have been an attempt to distance themselves from any accusation of poisoning their patient. The Earl of Essex had recently accused the queen’s physician, Spanish-born Roderigo Lopez, of trying to poison her. A show trial convened by the earl had ensued, and Lopez had been convicted and executed, despite being innocent. In the light of the paranoia surrounding the Lopez affair, the doctors were probably trying to shift any suspicion of poisoning away from themselves. They may have reasoned that the diagnosis of witchcraft and enchantment could in no way be blamed on them. It should be noted that our contemporary understanding of their treatments, while not having caused Ferdinando’s death, may well have hastened it.

If it was poisoning, the question arises as to who was responsible for his death. Perhaps disgruntled Catholics, angered by his surrender of Hesketh to the authorities, would be the chief suspects. As has already been noted, this ill feeling had already caused a rift between Ferdinando and some of his servants, who had fled to the protection of the Earl of Essex. In reprisal, Ferdinando had at least one of the the men’s family home searched, and reported his suspicions to the authorities. No further action was taken against any of the servants, much to Ferdinando’s frustration, and he was accused of over-overstepping his authority. It could very well be that the banished servants had accomplices still within Ferdinando’s household who could have administered the poison.

The other possibility (although less likely) is that members of Elizabeth’s government itself wanted his demise. As noted above, Lord Burghley had never trusted Ferdinando, with the rumours of plots and treason swirling around him. He may have also reasoned that to get rid of Ferdinando would damage his family politically. Indeed, the Stanley family was severely weakened after Ferdinando’s death. This was because his widow Alice rapidly entered into a legal dispute with his brother William, the new Earl of Derby, as to who inherited Ferdinando’s lands and property. The lengthy and costly wrangling set the family back both in terms of local and national influence.

These two possible conspiracies above lack concrete evidence, and perhaps the truth around Ferdinando’s demise will never be known. The unsolved nature of the suspected poisoning has continued to intrigue people even to the present day. A scientific paper in medical journal The Lancet, appearing in 2001, suggested which poisons could have been used to carry out the deed. A full length academic book entitled The Assassination of Shakespeare’s Patron was published in 2011, which looked in detail at who would benefit from Ferdinando’s demise.

What Next for Lord Strange’s Men?

With Ferdinando’s death, his acting troupe had been placed in a very difficult position. However, their fortunes rapidly improved in the months that followed. As noted above, Ferdinando’s brother-in-law, George Carey, had headed the official enquiry into his death. His father was Henry Carey, the Lord Chamberlain, responsible for official entertainment at Queen Elizabeth’s royal court. Seeing the value of Lord Strange’s Men as accomplished actors, he took them on as his own troupe. Accordingly, they were renamed the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. The original core members of Lord Strange’s Men, namely Augustine Phillips, William Kempe, George Bryan, Thomas Pope, John Hemmings and Henry Condell were now joined by actors William Shakespeare and Richard Burbage, all as sharing players. At the same time, Edward Alleyn left for a rival troupe. That winter, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men resided at the Cross Keys Inn, familiar to most of them from their early days in the previous group. As well as the eight sharing players, their number was boosted by a further eight hired actors to perform smaller roles, plus some boy apprentices.

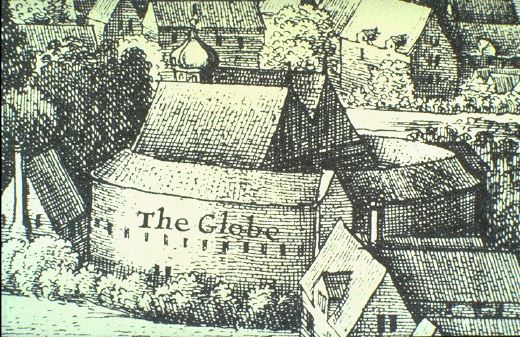

In the next six years, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men would go on to perform at Shoreditch’s The Theatre, The Curtain Theatre, and The Globe, the latter being able to hold an audience of 3000. During this time, they performed Shakespeare’s new plays of Love Labours Lost, The Merchant of Venice, Julius Caesar, Henry V, Richard II and Hamlet. Although their patron Henry Carey died during this time, his son George took over both the role of Lord Chamberlain and the patronage of the troupe, and accordingly they continued under the same name.

At the end of this busy period, both George Bryan and Thomas Pope retired from acting. William Kempe also left, but perhaps under a cloud. Kempe was known for his portrayal of the comedic roles in Shakespeare’s plays. There are hints (from comments in Hamlet) that Shakespeare had wearied of clowning improvisation in his plays. Kempe proceeded to perform his own Nine Day Wonder, where he Morris danced from London to Norwich, often greeted by cheering crowds, as he covered the 110 mile route.

The Essex Plot

In 1601, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men became caught up in a treasonous plot against the queen. The Earl of Essex had recently been disgraced for his military failure in Ireland. He had been tasked with quelling an uprising there, but instead had made peace with the rebels. For this, the earl was punished by the queen by being banned from her court, and had his lucrative monopoly on the sale of sweet wine in England confiscated. Facing financial ruin, he further alienated Elizabeth by writing pleading and then angry letters to her.

When this approach failed, he began to scheme against the queen. Together with a group of eight nobles loyal to him, a plot was hatched to capture the Tower of London, the queen and her court. The plan was to force her to sack those people that had crossed Essex politically and promote him to the positions he coveted. He further wished to compel Elizabeth to name King James VI of Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots’ son, as her heir. (Following the above discussion on Henry VIII’s will, this would be following the line of his older sister Margaret, who had married into the ruling Stuart kings of Scotland.)

To rally the people of London to their cause, the earl’s conspirators approached the Lord Chamberlain’s Men to participate in a bout of propaganda. They persuaded the actors to perform one of Shakespeare’s most controversial plays, Richard II, in which the monarch was both deposed and then killed. The performance took place on 7th February, and the next day the rebellion commenced. When Essex entered into the city with 200 of his followers, he soon realised he would be unable to gather the support he needed. The attempted coup was a complete failure, as Elizabeth’s government had already been tipped off. Essex retreated back to his house, where he was besieged and subsequently arrested.

There was a rapid government inquiry into the affair. Augustine Phillips, as one of the most senior of the sharing players, was summoned to appear. He stated that the actors had not wanted to perform Richard II, saying it was an old play, and so they thought there would not be much interest in it. They had been swayed by being offered a much higher fee than they would be normally, and so had agreed to go ahead with the performance. Fortunately, Phillips’s expression of ignorance over the motivation of those wanting the troupe to stage the play was believed, and they were not punished. The Earl of Essex was executed, along with four other conspirators, just a few weeks after the incident. Other plotters were imprisoned or heavily fined. There was clearly no ill will towards the Lord Chamberlain’s Men though, as they performed for Queen Elizabeth the night before Essex’s execution.

The King’s Men

In 1603, Queen Elizabeth passed away, after forty-four years of reign. Going against her father Henry’s wishes as laid out in his will, she chose a Scottish Stuart king as her heir. This was Mary Queen of Scots’ son, King James VI of Scotland, who became King James I of England. He took over the patronage of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, changing their name to the King’s Men. There were now just three of the original Lord Strange’s Men within the troupe: Augustine Philips, John Heminges and Henry Condell. William Shakespeare remained, probably no longer as an actor, but as the King’s Men’s full-time playwright. Richard Burbage, who had joined the Lord Chamberlain’s Men at the same time as Shakespeare, was by now the leading actor of the troupe. Having played Hamlet, he would go on to perform as Othello, Macbeth and King Lear.

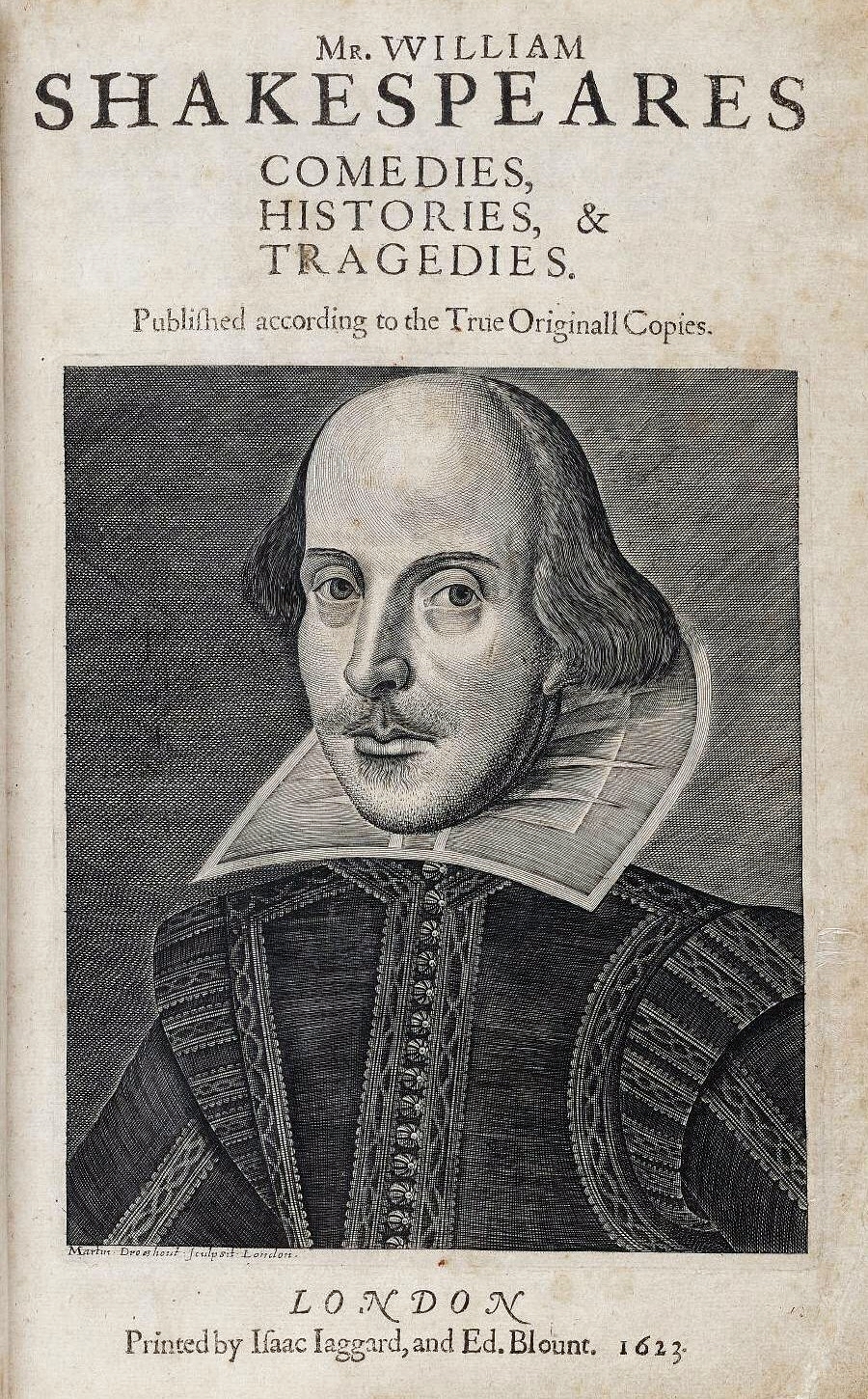

Two years later, Augustine Phillips died leaving money in his will to Shakespeare, Burbage, Condell and Heminges, along with other members of the group. The last two remaining members of Lord Strange’s Men, Henry Condell and John Hemminges, were young men when they had first joined the original troupe, and so would continue with the King’s Men for many more years. In 1623, they published one of the most important documents relating to Shakespeare that has survived through history, the First Folio.

The First Folio was the first complete collection of all 36 of Shakespeare’s plays. Although some had been published before, the text of 20 of them had never appeared in print. These included Macbeth, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, Twelfth Night and Measure for Measure. Of the 750 copies printed, only 235 now remain (one of them residing at Stonyhurst College and on view in their library which occasionally opens to the public). Hemminges and Condell as the First Folio editors stated that the book replaced any earlier publications which they dismissed as “stol’n and surreptitious copies, maimed and deformed by frauds and stealths of injurious impostors”.

Importantly too, the First Folio names the sharing players that were the principal actors in Shakespeare’s plays. After William Shakespeare and Richard Burbage, the first names to appear at the very top of the list are those of Lord Strange’s Men: John Heminges, Augustine Phillips, William Kempe, Thomas Pope, George Bryan and Henry Condell. The subsequent actors listed are those that were members of the King’s Men, and the troupe would continue to flourish throughout the reign of King James I and his son King Charles I. Indeed, they continued until the latter king’s execution, only ceasing when the Puritan Parliament closed all theatres during the Civil War and Commonwealth Period under Oliver Cromwell. Puritans did not approve of people ‘pretending’ to be something they were not, so actors were viewed with extreme suspicion.

Postscript: Shakespeare in Lancashire?

There has been much speculation by historians as to whether William Shakespeare journeyed with Lord Strange’s Men up to the Stanley homes of Lathom and Knowsley. It may have been that he even performed with the troupe himself, as he did in the subsequent incarnation of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. At the time of Lord Strange’s Men, he would have been at the very beginning of his career as a playwright.

As has been stated above, Lord Strange’s Men were the first company to perform Henry VI (part 1). It is likely that the three subsequent historical plays, Henry VI (part 2), Henry VI (part 3), and Richard III, were written when Lord Strange’s Men were active, with Ferdinando still as their patron. Part of the evidence comes from the fact that the Stanley family feature favourably in these plays, as instrumental in the foundation of the whole Tudor dynasty. The play of Richard III depicts the men of the Stanley family bringing Henry Tudor to England, intervening at the critical moment to ensure his victory at the Battle of Bosworth and the killing of King Richard III. Subsequently, they were instrumental in arranging the marriage of Henry Tudor (who had become King Henry VII) to Elizabeth of York, bringing into alliance the two warring families and ending for good the Wars of the Roses. Clearly writing with his patron Ferdinando in mind, this could be Shakespeare flattering the Stanleys and holding them up as the rightful determiners of history. In reality, during the Wars of the Roses, the Stanleys were constantly playing a double game. They had supported both the Lancashire and York factions during the conflicts, and would swap sides when it suited them to further their own interests.

There are other tantalising clues in Shakespeare’s work, such as a reference to a deer park in Love’s Labours Lost that resembles Knowsley Park, and with the principal character being a ‘King Ferdinand’. The ‘fusspot’ character of Malvolio in Twelfth Night is thought by some to be based on the Stanley’s steward William Farington (pictured earlier in this piece), who Shakespeare could have met if he had been at the family’s household with the rest of Lord Strange’s Men.

When Titus Andronicus was published, it was dedicated to Ferdinando, along with two other nobles. At this point, Shakespeare was probably hedging his bets as to who would be his patron in the future. After Ferdinando’s untimely death, his brother William became the 6th Earl of Derby. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men in Greenwich at William’s marriage celebrations to Elizabeth de Vere. Elizabeth was the granddaughter of Lord Burghley, which may seem a surprising match given his distrust of the Stanleys. Perhaps he believed that as, at that time, William was a plausible heir to the throne, maybe it was a case of ‘keep your friends close, and your enemies closer’.

William set up his own troupe, who went by the name of Derby’s Men. It is known that he wrote plays for them, as the Jesuit spy George Fenner commented that the earl was “busye in penning comedyes for common players”. After Ferdinando’s death, many of the dissident Catholics living abroad transferred their hopes to him as next in line for the throne, but as has been seen, Elizabeth chose a Stuart king instead.

As well as performing at his own houses in Lancashire, Derby’s Men went on tour around the country. The King’s Men also toured outside of the capital, including coming to Lancashire and Cheshire on a regular basis. In the early 1610s, they were performing alongside Derby’s Men at Congleton’s Swann Inn, and in the 1620s at Dunkenhalgh Hall in Clayton-le-Moors. Records show that William Stanley paid the King’s Men on these occasions.

Today there is an ongoing strong link with William Shakespeare in Lancashire. The incredible Shakespeare North Playhouse in Prescott was completed in 2022. This is a ‘theatre-in-the-round’ and is based on the plans of a theatre from the time of James I and Charles I. It stands very close to Knowsley Hall and the 19th Earl of Derby, Edward Stanley, is president of the trust that runs it. As well as regularly staging Shakespeare’s plays, it also hosts a variety of contemporary works, including music and comedy. Its own fascinating history, linking back to a Jacobean Prescott theatre from the time of William Stanley, will be the subject of a future (much shorter!) piece on this site.

Written by A. Bowden 2025

Unless otherwise stated, all images on this page are classed as Public Domain

Access

Shakespeare North Playhouse is open Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. The shop and cafe are always open on these days. The interior of the Shakespearean theatre can be viewed by booking a heritage tour, or attending one of the many performances. See the website here

Knowsley Hall, the seat of the Earl of Derby and Stanley family, opens for guided tours for a few days each August. See here

Lathom House only has one surviving wing, dating from the 1730s. This is now private residential apartments.

Nearby to the house is Lathom Park Chapel. This was built by the 2nd Earl of Derby and would have been used by the Stanley family. It is open on Sundays, May through to September 2pm-4pm. See here

References

Main Sources

Lord Strange’s Men and their plays, Lawrence Manley and Sally-Beth Maclean (2014) Yale University Press. This is the definitive book on Lord Strange’s Men.

The Earls of Derby and the Early-Modern Performance Culture of North-West England, Elspeth Graham (2020) Shakespeare Bulletin. Elspeth Graham is a professor at Liverpool John Moores University, and a specialist on the Stanleys and their Shakespeare connections. A free pdf version of this paper is available online.

Brief Chronicles Vol III Peter W. Dickinson (2011) p.254. Review of The Assassination of Shakespeare’s Patron by Leo Daughtery, Available online as a free pdf file.

Living History with the Countess of Derby podcast. Episode 2: The Earls of Derby and Shakespearean Theatre 1580-2023

Additional Sources

Shakespeare and Lancashire

ljmu.ac.uk/about-us/news/articles/2016/4/29/shakespeare-north-gets-planning-permission

knowsleyhallvenue.co.uk/shakespeare-and-the-earls-of-derby/

shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/shakespedia/shakespeares-plays/loves-labours-lost/?gad_source=1

bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5HPK8vQTZ0DHmFlYFZ7jHHj/lancashire-family-prove-pivotal-to-shakespeares-players

The Rose Theatre Residence

losttheatres.net/rose

bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/8L8sDc4ZjblMbP4cnLBLMS/blossoming-at-the-rose-theatre

shafe.co.uk/welcome/art-history/tudor_contents/tudor_13_-_tournaments_and_royal_progresses/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Marprelate

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marprelate_Controversy

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1592–1593_London_plague

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Globe_Theatre

The Acting Troupes and Their Players

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Strange%27s_Men

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Strange%27s_Men#Derby’s_Men

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Chamberlain%27s_Men

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King%27s_Men_(playing_company)

shakespeare-online.com/biography/edwardalleyn.html

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustine_Phillips

lostplays.folger.edu/Category:George_Bryan

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bryan_(actor)

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Kempe

lostplays.folger.edu/Category:Thomas_Pope

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Pope_(actor)

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Condell

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Heminges

The Poisoning of Ferdinando

isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/people/lords/ferd_dth.htm

thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(00)04961-8/abstract

Miscellaneous

rsc.org.uk/shakespeares-plays/histories-timeline/timeline

Comments are closed.