Visitors to Appley Bridge may be intrigued to see street signs informing them they are travelling along Skull House Lane. It is named after an old large house, which has had a skull in residence for as long as anyone can remember. But what is the origin of the skull, and why has it been kept within the building for so many years?

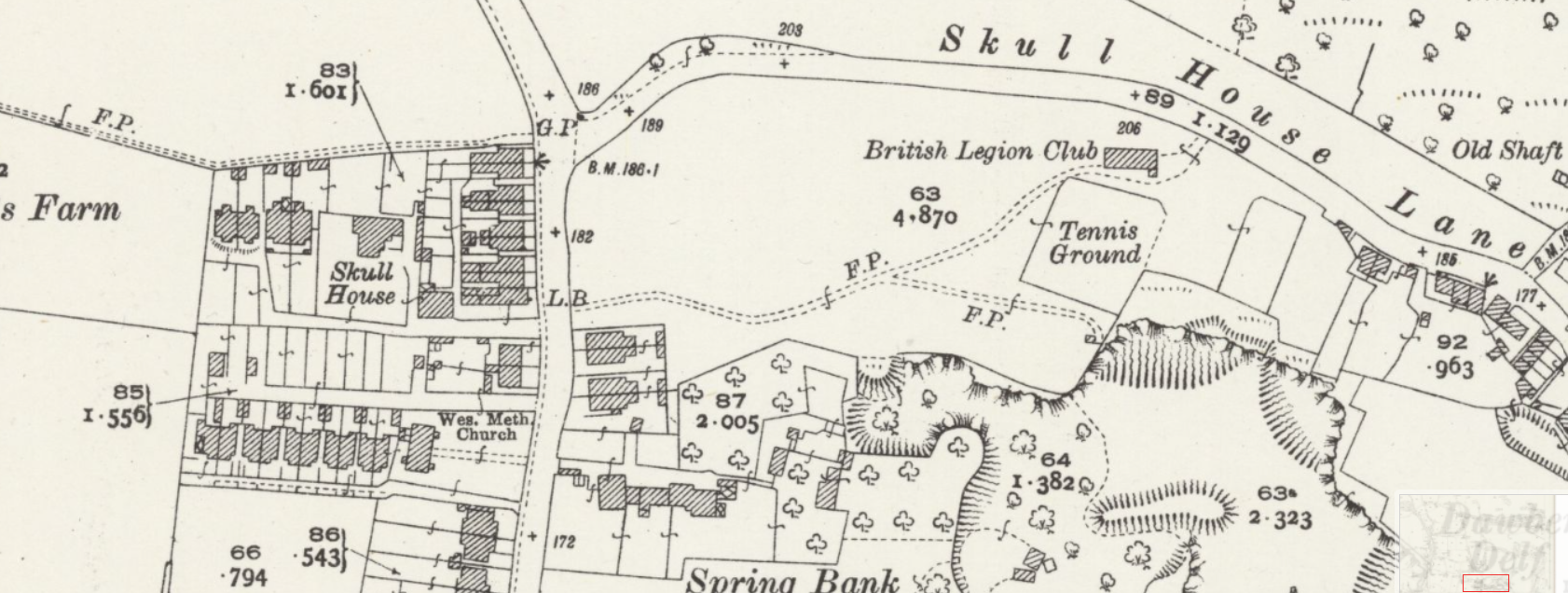

Confusingly, Skull House does not lie on Skull House Lane. The lane actually ends where it meets Appley Lane North, and Skull House stands just a short distance from this junction, in what would have been fields when it was first built. The route of Skull House Lane does carry on past the house, but today it is merely a public footpath and not a road for vehicles.

Skull House dates from the late 1600s, and has had alterations in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was constructed using cruck frames, and still has some of its original mullioned windows. It seems to have been later split into two or three properties. The central one is named Skull House, with End Cottage attached at one side and Skull House Cottage on the other (this has a plaque inscribed Skull House Cottage on its gable).

Author Peter Underwood wrote this description of the building in the 1970s: “It is a strange house, full of walls riddled with mysterious cupboards; chimneys that lead goodness knows where; leaded windows decorated with skulls; a door more than four hundred years old; low ceilings; massive beams; odd corners and nooks and crannies; a priest’s hole; a hollow beam and boarded-up underground cellars”.

That most of the fabric of the house is old is not in dispute. What is not clear is why it has a skull residing within the building. Local folklore books that mention the skull usually list two possible origins for it. The first is an implausible tale featuring a knight from the legend of King Arthur, the second an unlikely story featuring some of Oliver Cromwell’s soldiers.

The Time of King Arthur?

The first story states that four knights once lived in a house on the site of where Skull House is today, in the time of King Arthur. One of them was the Knight of the Death’s Head, or Knight of the Skull, who had a human skull mounted on his helmet. It is said that this is the skull that now resides at the house, after the knight was killed.

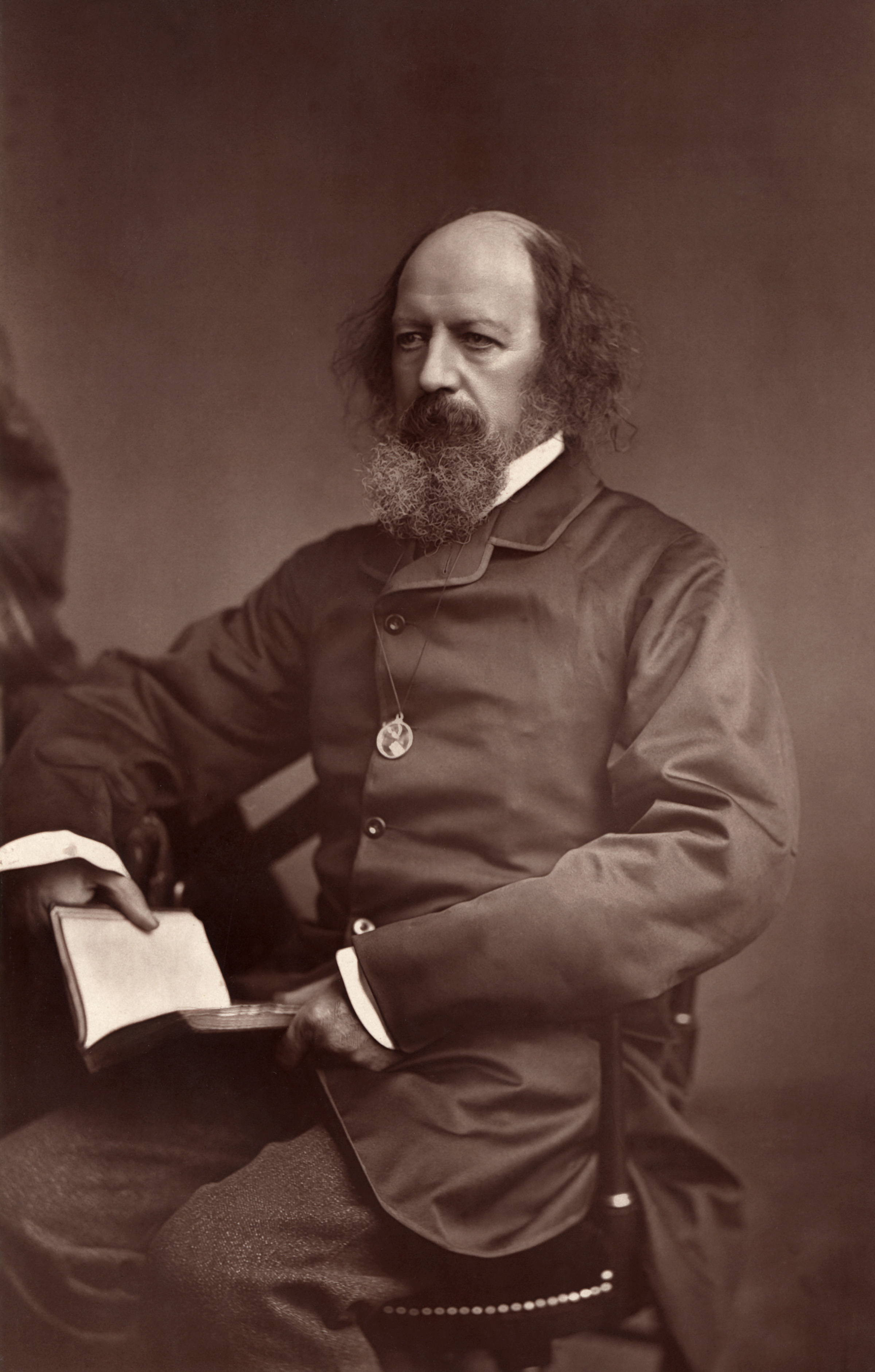

Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote the Idylls of the King, his version of King Arthur stories, which were published in 1859. Contained within it is the tale of Gareth and Lynette. Lynette comes to King Arthur, saying her sister is being held captive in Castle Perilous by four knights. Sir Gareth, who had been posing as a servant in King Arthur’s kitchen, volunteers for the dangerous task to vanquish the captors and rescue Lynette’s sister. His quest sees him defeat the first three knights, and then he finally faces the deadliest, known as the Knight of the Skull. He is described as being “a huge man-beast of boundless savagery”, wearing a helmet with a human skull on it, and having the figure of a skeleton on his arms.

In the fight Sir Gareth defeats him, splitting the skull in half in the process. The knight is revealed to be a young man who begs for mercy, blaming the other three knights, his brothers, for capturing Lynette’s sister in an effort to lure King Arthur and Sir Lancelot into a trap. The details in the episode are from Tennyson’s imagination, and based on the work of Thomas Malory’s story Le Morte d’Arthur (the death of Arthur) written some 400 years earlier. Malory’s version has more knights in it, but none are described as the Knight of the Skull, nor do any of them have a real human skull on their helmets. Regrettably, Castle Perilous was never located at Appley Bridge, and the only reason this story could have been connected in the originator’s mind is from a memory of Tennyson’s poem, perhaps learnt in school. Finally, King Arthur is a mythological figure, not a historical one, so the whole premise is implausible.

Cromwell’s Soldiers

The second explanatory story is said to have been unearthed by an unnamed investigator in 1937. This holds that the skull belonged to a monk who, being pursued by Cromwell’s soldiers, took refuge in the house. He climbed inside one of the chimneys, which led to a small room where he hid. Cromwell’s men started a fire in the grate, the smoke forced the monk out and he was summarily beheaded. His skull was allowed to remain at the house, the rest of his body is hidden elsewhere in the garden or the house.

The first thing to tackle with this story is that monks did not exist in England in the time of Oliver Cromwell. The monasteries had been abolished, and along with it the occupation of being a monk, in the time of Henry VIII, over a hundred years before Cromwell’s rule. However, other versions of the story state it was a priest, not a monk, that Cromwell’s soldiers were pursuing. Perhaps this was the original version of the tale, with a monk being later substituted for a priest, as ghostly monks are more ‘spooky’ in the popular imagination.

On the face of it, the same story with a priest being persecuted seems more plausible, but historically it does not seem likely. Cromwell and his puritan soldiers are convenient bogey men of history. In Cromwell’s time there were very few Catholic priests killed in England. The time when such men were persecuted was predominantly in the time of Queen Elizabeth I when around 150 priests were executed, and many more imprisoned. The policy continued to a lesser extent during her successor King James I’s reign. Catholic priests often visited houses in secret to perform mass during the reign of these two monarchs. They would often remain hidden to prevent being found, and numerous historic halls in Lancashire have priest holes to enable this.

The inconvenient truth is that it was the Church of England in the time of Elizabeth I and James I that was behind the persecution of Catholic priests, not Cromwell’s puritans. In the interests of balance, it should be noted that around 300 Protestants, many of them clergymen, were killed for their faith under the very short reign of Catholic Queen Mary, Elizabeth’s sister.

Another fallacy in the Appley Bridge story is the execution of the priest ‘on the spot’. Catholic priests were never executed immediately after being caught. They would be arrested, interrogated, put on trial and then executed if found guilty. During Elizabeth’s reign it became a crime to be a priest. On being caught in Lancashire they would be sent to Lancaster Castle for imprisonment , trial and possible execution, or alternatively dispatched to London. The vast majority of those killed are known by name, and the dates of their deaths are not in Cromwell’s time.

This particular story is similar to one told about Heskin House near Euxton, where once again Cromwell’s men are said to have killed a Catholic priest when they found him. It is interesting to note that Cromwell’s soldiers are often blamed for damaging religous effigies in churches, but again the destruction of stained glass, icons and biblical paintings was predominantly carried out during the reign of Henry VIII’s children, King Edward VI and Elizabeth I. This was done under the instructions of the Church of England who saw such things as ‘popery’, i.e. Catholic idolatry, and so worthy of destruction.

What this story perhaps taps into is the tradition of old Lancashire houses possessing the skull of a Catholic martyr. At Wardley Hall in Salford, owned by the Catholic church, the skull there is treated as a religious relic and is said to belong to St Ambrose (although it is by no means certain that it is his skull). At Mawdesley, another old building is known as Skull House, which once housed the skull that has been variously attributed to William Haydock, a Cistercian monk from Whalley, or George Haydock, a Catholic priest. It originated at Cottam Hall and was later removed to Mawdesley. Both these cases will discussed at a future date here on Lancashire Past.

Guardian Skulls

The most likely explanation for the skull residing at the house in Appley Bridge is given by Dr David Clarke in his PhD thesis The Head Cult: Tradition and folklore around the severed human head in the British Isles. He believes that skulls held in old houses can be seen as ‘Guardian Skulls’, that bring good luck to the house while they remain, but bad luck if removed. As to the origin of these skulls, he quotes Martin Smith, owner of Skull House in 1993, who had lived there since 1970. Mr Smith stated that he believed the skull would have been dug up in the 1600s when the house was originally being constructed as a high status home for a yeoman farmer. The skull would be seen as a form of protection for the home, and displayed prominently within it. Perhaps there was a sense of giving the skull a new home, as it had been disturbed from its previous resting place.

It is a common trope of stories about skull houses that the skull must not be moved from the house. A number of local folklore books state that the skull at Appley Bridge was removed, even on one occasion thrown in the River Douglas, but it would always mysteriously return to the house. Invariably, something bad would happen to the person who had tried to get rid of it. Very similar stories are told about the Timberbottom Skulls of Turton (see our page here for a discussion on their history and folklore).

Although Skull Houses usually have the reputation of being ‘haunted’, author Peter Underwood did not find this when he spoke with Mrs E. A. Unsworth, a previous resident of the house who had lived there for 25 years. She had kept the skull in a cardboard box, stored behind the old fireplace, and would show it to anyone that was interested. He said that she “scoffed at the idea of its having powers, and did not believe the house was haunted, although it had that tradition”. At the time of publication in 1977 of Underwood’s Ghosts of the North West, he spoke with Martin Smith, the then occupant, who said, “We have lived here for seven years but haven’t encountered any ghostly happenings yet!”.

As part of the Guardian Skull tradition, there is often a local belief that the skull must remain within the house, even when the owners change. In Jessica Lofthouse’s North Country Folklore, she stated that an owner had said to her that if they sold the house, the skull would have to go with it – or “no sale!”. When Dr David Clarke was doing some initial fieldwork for his PhD in 1990, he was told by a local man that if the skull was removed, the house would fall down.

A Prehistoric Origin?

The Appley Bridge skull is described as being “discoloured” and “brown and polished”. This hints that it had been buried in the ground for some time, and if it was in soil with a high peat content this could have led to the discolouration. One of the skulls at Timberbottom also has this dark brown appearance, as does the skull on display at the Packhorse Inn at Affetside, Bury. Baring in mind that the Appley Bridge skull could well have been dug up when the foundations of the 400-year-old house was being laid, in what contexts could it have been buried?

Since England was a Christian country from the time of the Anglo-Saxons, most skeletons would from then on be interred in a graveyard associated with a church. This means that the Appley Bridge skull could well predate Christianity. Professor Melanie Giles believes that many Guardian Skulls are prehistoric in origin, and are examples of Bog Bodies. These occur when a woman or man is deliberately sacrificed and immersed in a peat bog. Although full bodies have been discovered within this tradition, most of those known in Lancashire consist of only the skull being placed within the bog to be preserved. The rest of the body is disposed of in another way, perhaps being cremated. Worsley Man is a well-known example of this kind of ritual killing, and there are also examples from Red Moss near Horwich (see our page here) and Pilling (see here). The practice was commonest in the Iron Age, but also continued into the early Roman occupation of Britain, where the local tribes would continue with their pre-Roman beliefs.

If the Appley Bridge skull could be dated to the Iron Age, or the early Romano-British era, then it would point towards it being a Bog Body. Most other people in the Iron Age in Britain were not buried, in fact very few remains have been discovered as they were probably cremated and the ashes scattered. The Bronze Age in Lancashire has numerous recorded burials, but these are all cremated bone fragments within pottery urns, and never contain an intact skull.

The only way to be sure, would be to carbon date the Appley Bridge skull. No known specialist has examined it, although some of the books do assert that the skull is a female one, but give no evidence of who has determined this. Bog Body skulls found in Lancashire seem to have a fairly even split between male and female. For example, female ones were found at Pilling and Horwich, male ones at Astley Moss (Worsley Man) and Poulton. The most famous English bog body is that of Lindow Man from Cheshire, with Lindow Woman found nearby. There are two published photographs of the Appley Bridge skull, one in Kenneth Fields Lancashire Magic and Mystery, the other in Peter Underwood’s Ghosts of North West England. Readers who have access to those books (see the Reference section) may wish to compare male and female skull pictures on the very informative Future Learn website here to see if they can decide for themselves.

For those wishing to read more on Guardian Skulls, their folklore and possible links with Bog Bodies please see our page on the Timberbottom Skulls

Site visited by A. and S. Bowden 2025

Access

Please do not disturb the residents of Skull House. The house can be seen from the Public Footpath that passes beside it, just off Appley Lane North and opposite Skull House Lane. On street parking available on Appley Lane North.

Nearby

References

The Head Cult: Tradition and folklore surrounding the symbol of the severed human head in the British Isles, David Clarke (1999) PhD thesis, University of Sheffield. Available to download for free, as two pdf documents from: etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/3472/

Bog Bodies: Face to face with the past, Melanie Giles (2000) University of Manchester. Available to download for free as a pdf document from: library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/46717. Also available as a paperback book.

The Stripping of the Altars, Eamon Duffy (1992) Yale University Press

Ghosts of North West England, Peter Underwood (1978) Harper Collins. Republished as an eBook in 2018 and available very cheaply.

Idylls of the King: Gareth and Lynette, Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1859). Available online at kalliope.org/en/text/tennyson1999063003a

North Country Folklore, Jessica Lofthouse (1976) Hale

Lancashire Magic & Mystery: Secrets of the Red Rose county, Kenneth Fields (1998) Sigma Leisure

historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1073003?section=official-list-entry

theguardian.com/books/2022/jul/31/has-history-got-it-wrong-about-oliver-cromwells-persecution-of-catholics

maps.nls.uk/view/126520175

futurelearn.com/info/courses/forensic-facial-reconstruction/0/steps/25656

your.westlancs.gov.uk/?uprn=100012417837

Comments are closed.