Brindle Lodge is a late Georgian hall set within its own parkland. Although the house is privately owned, the historic parkland is open to anyone, criss-crossed by public footpaths and local trails. There is much of interest to see within its bounds, and the history of the ownership of the house itself is a fascinating one.

The house and grounds were created by William Heatley in 1808. Squire Heatley, as he was locally known, was a former captain in the Lancashire Rifle Volunteers. He came from a wealthy family that owned land in Samlesbury and Brindle. Their money had come through investments in funds, particularly when prices of them were very low during the Napoleonic wars, and later vastly inflated.

A bachelor for all of his life, Heatley spent his time and money supporting the Catholic church. In 1814, he set up an education fund of a thousand pounds for Ushaw College in County Durham, a training college for Catholic priests. This had only opened six years earlier and would last for two hundred more. Closer to home, he financially supported the churches of St Alban’s in Blackburn, St Augustine’s in Preston, St Patrick’s in Manchester and a chapel at Osbaldeston.

Heatley’s local church was St Joseph’s, a mere couple of minutes walk from Brindle Lodge itself. In 1832, he paid for an enlargement to the building with the addition of the Lady Chapel. Father Bede Smith was the priest in charge at the time and was surely grateful for the donation. However, if he thought patronage might continue with the new owner of Brindle Lodge after Heatley’s death, he was sorely mistaken.

When Squire Heatley passed away in 1840, aged 76, a broadside ballad entitled Lines on the Death of William Heatley, Esq., of Brindley Lodge was published in tribute to him, penned by a ‘D. Marquis’. It begins:

The great and worthy Heatley’s gone! The generous and the brave! His noble soul has gone aloft ,- His body to the grave.

A better man was found nowhere, That we could see or name – For he was eyes unto the blind, And feet unto the lame.

His open hand – his generous heart, Was ready at his door: No matter what their creed or name, If they were needy poor.

The broadside continues for another eight verses before concluding with:

Tho’ genorous worthy Heatley’s gone! And bid this world adieu – Some noble soul will take his place, Both genorous kind and true.

The details of Heatley’s will immediately caused consternation from his relatives, and to reflect this The Brindle Lament: A Dogged Ballad was also published. This told the sorry tale of how Thomas Eastwood, his nephew-in-law, claimed that Heatley had been put under undue influence by a cleric to leave the most of his money to the church, cheating the relatives out of that which was rightly theirs.

The Eastwoods Dispute the Will

Heatley’s closest relatives were his two nieces, Catherine Anne Eastwood and Alice Maria Middleton. Both were named beneficiaries in the will. Heatley had left Brindle Lodge to Catherine along with 330 acres of land in the neighbourhood, which would bring in a considerable rental income. Her husband Thomas Eastwood took great exception at their not being given more of Heatley’s immense wealth. The bulk of his money he had bequeathed to his close friend and spiritual advisor, Reverend Thomas Sherburne, for use in church and charitable purposes. Heatley had met Reverend Sherburne when the latter worked at the Blackburn Catholic mission, and they had become very close. At the time of Heatley’s death, Sherburne resided at The Willows in Kirkham.

Following litigation by Thomas Eastwood, Reverend Sherburne offered a compromise and handed over £6000. This was not the end of the matter though, and Eastwood continued to press his claim. To defend himself, Reverend Sherburne wrote a letter to The True Tablet (a Catholic newspaper). The publication then carried Eastwood’s repost and also Sherburne’s rejoinder to that.

Eastwood drew up petitions for his claims for more of Heatley’s wealth and sent them to a Bishop Brown of the Lancashire District. The petition to the Bishop had 194 signatories drawn from St Joseph’s congregation (which totalled 845 people). In 1844, his petition reached the House of Commons. It seems that a subsequent ruling by a Select Committee went in Eastwood’s favour, as documents show that Reverend Sherburne later appealed its findings to the House of Lords.

While all this was continuing, Reverend Sherburne continued to dispose of Heatley’s wealth, donating a further £800 to Ushaw College. A much larger amount was used to build Sherburne’s grand new church of St John the Evangelist at Kirkham. This was designed by the celebrated architect A.W.N. Pugin, famed creator of the clock tower of Big Ben and the interior of the Palace of Westminster. The church still stands today.

Thomas Eastwood’s Campaign Against St Joseph’s

Thomas Eastwood proceeded to needle Father Bede Smith of St Joseph’s Church by refusing to pay his pew-rent, having taken over the rights to Squire Heatley’s seat. In retaliation, six members of the congregation barred his entry to the chapel. Eastwood subsequently claimed that in doing so they had assaulted him. They were charged and convicted of assault, but refused to pay their fines. At the Chorley Petty Sessions in March 1846, the men were committed to the Preston House of Correction for non- payment of the money. They in turn took action against the Magistrates for false imprisonment, but their claim was withdrawn on technical grounds.

Eastwood became more creative in his campaign against St Joseph’s. He attempted to close the path through his parkland to the church. When he found he could not legally do this, he posted men to watch before and after service times so that anyone straying off the path onto his grounds would be prosecuted.

At the end of the affair, Thomas Eastwood renounced Catholicism and became a Protestant. He converted the Brindle Lodge domestic oratory (a prayer room in the house) into a bathroom and lavatory. He also removed two of his sons from college where they were studying to become Catholic priests. Lastly, Eastwood began to worship at Brindle St James, but before long quarrelled with the rector there too. Sadly, records do not tell what his wife Catherine thought of his behaviour but, given the position of even wealthy women in Victorian society, she probably had little choice but to go along with it.

Thomas Eastwood remained proud and protective of Brindle Lodge. A lithograph of the house appeared in an 1846 edition of The Mansions of England and Wales, illustrated in a series of views of the principle seats in the County of Lancashire published by Edward Twycross. The house is shown in a typical pastoral scene, surrounded by a large field, with cows sheltering from the heat under large trees. It is probable that the Eastwoods would have subscribed to a copy of this book, which showed off their recently acquired landowning status. The lithograph is entitled Brindle Lodge, the Seat of Thomas Eastwood Esq(uire).

When Brindle was suggested as a site for a new army barracks building, Eastwood wrote to the Secretary of State objecting. Initially, a site in Blackburn had been purchased and marked out for development, but its close proximity to factories deemed it unsatisfactory. Mellor was then mooted, followed by Brindle. Eastwood stated in his letter that “the mansion would thereby be materially reduced in value” if the plans were to go ahead. Instead Fulwood was chosen, and the barracks there were built in 1848.

Thomas Eastwood died in 1867 and was buried at St Leonard’s Church, Walton-le-Dale. His widow Catherine organised an auction of all the contents of Brindle Lodge, including William Heatley’s extensive library. She then sold the house and surrounding estate.

The Whiteheads

Brindle Lodge was sold to a Mr Whitehead, a wealthy coal merchant from Preston. A descendant named Thomas Whitehead lived at the house until his death in 1937, aged 84. He worked at the firm of Whitehead, Marsden and Hull at Winckley Square in Preston. He also had mining interests, being listed as an associate member of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers. A keen cricketer, he is recorded as playing for Lancashire Cricket Club.

Teresa Travis in her memoir Sexton’s Daughter Comes Home relates that in 1947 there was an exceptionally cold winter. Her brother-in-law George was working as an undertaker, and his duties on a day following heavy snowfall involved having to bring a body to St Joseph’s Church from Gib Lane in nearby Hoghton. The snow drifts were so deep that the usual road to the church could not be taken. Mrs Whitehead, the then owner of Brindle Lodge, was asked if the body could be brought via her long driveway that ran from Hoghton Lane (the main road between Preston and Blackburn) to the church. The driveway is now a public footpath and quite possibly was then too but, for whatever reason, she refused. This meant that the coffin had be brought via the small village of Gregson Lane. With no road passable, the only route was over farm fields. With great difficulty, the coffin was dragged on a sledge through the snow to the graveyard. The experience badly affected Teresa’s brother in law, and he left the undertaking profession soon after.

Nurse Training College

During the 1950s and 1960s, Brindle Lodge was used as a residential college for nurses, for the initial part of their training. One retired nurse recalled how she spent three months living there, along with twenty other nurses. The bedrooms had been made into dormitories that could sleep four or five trainees. Another retired nurse remembered how the regime there was very strict, and how the trainees were only allowed out on Wednesday evenings, and had to be back by 9.30pm. The nurses were driven to Preston Royal Infirmary or Sharoe Green Hospital every weekday for work. Brindle Lodge continued as an NHS training college into the early 1990s, with some of the associated farm stables being converted to single bedrooms. It was then sold and has since become a grand domestic dwelling once again.

Visiting the Parkland Today

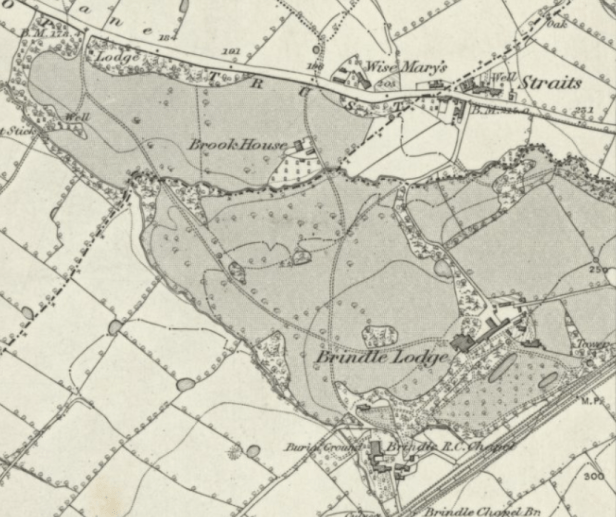

There are good views of the grade II* house set within its parkland from the public footpaths that cross the estate. Built of sandstone, it is of a symmetrical, classical Georgian design. The front of the house has a wide central porch with six tall sashed windows on the ground floor, and seven above. There is also an associated tower folly but this cannot be seen from any of the footpaths. However, a few years ago, local historian, Steve Williams, was granted permission to enter and take photographs of the tower, with its enigmatic carvings. See the page on the Chorley Historical and Archaeological Society website here.

Brindle Lodge has a gatehouse, the driveway of which is a public footpath that once acted as the main carriageway to the house from Hoghton Lane. By walking this, the visitor can see the parkland laid out either side. There are woodlands of Beech, Oak and Holly to the right of the driveway, which have locals’ paths through them. The banks of the brook that runs through the woodlands are full of Celandine, Wood Anemone and Wild Garlic in the spring.

Either side of the driveway are hay meadows and, as the house is approached, tall trees line it, including large specimens of Turkey Oak. St Joseph’s Church is a couple of minutes walk away from Brindle Lodge, just off the main drive and linked to it via a public footpath.

Suggested Walking Route

Park at the recreation ground and playing fields on Gregson Lane (free parking). The Cafe on the Green next to the car park is open every day except Monday (see here).

Head up past the new community centre and children’s play area. There is a public footpath that runs in front of a small row of houses here. Turn left onto this path. Follow it as it passes the back gardens of some more houses. The path becomes narrow as it runs between back garden fences and a hedge, but it soon reaches an open farm field. Keep on the path as it runs along the left hand side of the field. The path then drops down into woodland and reaches a wooden footbridge. Cross the footbridge over Black Brook and head up the slope to meet the public footpath of Brindle Lodge driveway. Turn left and walk for a couple of minutes to see the gatehouse (privately owned). Then retrace your steps back along the driveway and head towards the hall. Cross the cattle grid by the small stone bridge over the brook, and then climb the rise, keeping to the driveway. Brindle Lodge can be seen on the left. The driveway terminates (for the public) before a closed gate. At this point turn left at the metal kissing gate onto a public footpath and follow this for a short while for better views of Brindle Lodge.

With the view of Brindle Lodge before you, notice how the footpath is in a dip. The parkland fields look landscaped here, perhaps hiding from sight the farm buildings from the hall. However, the view from the hall would be a pastoral one of cattle grazing in the meadows, and then looking over to the Bowland Fells in the distance.

Now retrace your steps back to the driveway, and cross over it to follow the public footpath to St Joseph’s Church, which is a very short walk away. Go through the kissing gate at the pre-rusted railings. Follow the lane to reach the imposing entrance to St Joseph’s. Just to the right of the building there is a little-known Medieval boundary cross, from nearby Haddock Park Wood (see our page here).

At this point, the walker has a choice of retracing their footsteps to go back the way they came to Gregson Lane, or you can make the walk circular. Those wishing to make the walk circular should head past St Joseph’s Church (keep the building on your right) and pass between its associated cottages. Note the interesting carvings on the garden wall of the cottage on your right. Head under the railway bridge.

At the T-junction, turn right. Be aware that this lane has occasional motor and farm vehicles on it, but it is a popular walking route despite there being no pavement. The name of the lane is Private Road – but don’t worry, it is not private! Its confusing name comes from the time when it was part of Brindle Lodge estate and the gates to it would be closed once a year, then giving it a nominally ‘private’ status. It is now is a public highway.

At the end of the lane turn right, and head over the railway crossing (the barriers descend when a train is coming). This becomes the Gregson Lane road and will bring you back to the recreation area, car park and cafe on your right.

Site visited by A. and S. Bowden 2023

Access

Brindle Lodge and its gatehouse are both privately owned, but the main driveway and many of the paths around the parkland are public footpaths. There are also locals’ paths in the parkland and woodlands as well.

Park at Gregson Lane recreation ground and playing fields (free parking), and use the suggested route above to reach the historic parkland. The Cafe on the Green at Gregson Lane serves drinks, snacks and light meals (see here).

Nearby, just a short walk away

A short drive away

The Strange Tale of Edward Kelley at Walton-le-Dale

Walton-le-Dale Lost Roman Military Site

References

William Heatley

A Literary and biographical history, or bibliographical dictionary, of English Catholics from the breach with Rome, in 1534, to the present time, Volume III, Joseph Gillow (1885-1902) London Burns & Oates. Available at wellcomecollection.org/works/ns38esy9 or archive.org). This source is the principle source covering William Heatley’s donations and the subsequent dispute over his will

historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1072574?section=official-list-entry

Lines on the Death of William Heatley,Esq– the ballad written just after his death

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ushaw_College

british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol6/pp75-81

chorleyhistorysociety.co.uk/nwsvws16/nwsvws1601.htm

maps.nls.uk/view/102343970

Thomas Eastwood

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/0016f840-a3c2-4933-8ffa-056b71687ad7

thetablet.co.uk/other/history-of-the-tablet

plantata.org.uk/obits/willson/smith_b.htm

lan-opc.org.uk/Walton-le-Dale/stleonard/burials_1868-1874.html

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_John_the_Evangelist%27s_Church,_Kirkham

Whitehead Family

Sexton’s Daughter Comes Home, Teresa Travis (1995), published by Anne Bradley and Claughton Press

prestonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/members-articles

espncricinfo.com/cricketers/thomas-whitehead-22933

dmm.org.uk/transime/u59-a.htm

redrosecollections.lancashire.gov.uk/view-item?i=255658&WINID=1690142925388

Nurse Training College

prestonhistoricalsociety.org.uk/pdf/phs-newsletter-15-.pdf

lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/news/873173.40-years-of-loyal-service/

francisfrith.com/uk/brindle-lodge

bbc.co.uk/lancashire/content/articles/2006/02/07/spooky_brindle_lodge_feature.shtml

Comments are closed.