The Heysham Hogback is an enigmatic Viking Age stone monument discovered in the 1800s. For years it lay outside St Peter’s church, and older locals of the village remember playing on it. It now rests within the church, carefully preserved for posterity. While its actual origins are unclear, historical opinion is that it could have been made in honour of a Viking chief or wealthy coastal trader. Hogbacks are rare monuments, with only a handful in Britain, most concentrated in Northern England and Southern Scotland. Despite their clear Viking links, intriguingly there are none found in Scandinavia.

The monument was created in the early to mid 900s, a time of considerable Viking influence on the North West coast of England. The Vikings in this part of the country were originally of Norwegian heritage, but had established strongholds in Dublin and the Isle of Man, both a short distance across the Irish Sea. While the material remains of their settlements are long gone, some of the stone monuments they carved have been preserved. Close to Heysham are the famous Sigurd Cross at Halton and the partial remnant of another hogback stone at Bolton-le-Sands (the links take you to our pages on these).

What Do Hogbacks Represent?

The name ‘Hogback’ is a Victorian creation, named after the shape of a large boar. However, the true meaning of the shape to a Viking observer can only be guessed at, though perhaps with some accuracy. Professor Howard Williams, a historical expert on the monuments of the dead, states that the shape has not one, but a number of meanings. Most obviously a hogback looks like a chieftain’s hall from the Viking age, complete with a tiled roof, a feature seen on many hogbacks. He further states that they could also represent something much smaller such as a shrine to a revered person, or a large casket that would hold precious artefacts.

Hogbacks usually have powerful creatures at either end of them, often bears. The ones at Heysham could be bears, but their limbs seem rather small. However, they uncontestably have very powerful jaws. Professor Williams believes that the end beasts act as spiritual guardians to ward off demons, and so protect the monument. He further argues that the overall hogback shape boasts both strength and protection, with its strong ridge along the top forming a protective canopy. There is a functional aspect to the very heavy stone too, as if it was a grave marker it would prevent desecration of the body or the burial goods beneath. An early report claimed a skeleton and a corroded piece of iron – probably a spear head – were found under the Heysham hogback, but some doubts have been expressed as to the veracity of this.

What do the Carvings Mean?

What is much more contentious are the meanings of the carvings. Human figures, four legged animals, birds, and seemingly abstract patterns cover both the main sides and parts of the roof. Scholars are still very much divided on how to interpret them. After its discovery, the first ideas put forward were ones based on Christian beliefs. For example, for the side featuring a single human figure it was suggested that this was Adam naming the animals. However, Christian interpretations have fallen from favour in more recent years because they don’t seem to adequately explain the scenes. Instead, It has been stories from the Viking world that are increasingly scrutinised to see if they could offer a clearer picture of what the carver intended to convey.

Sigurd the Dragon-Slayer

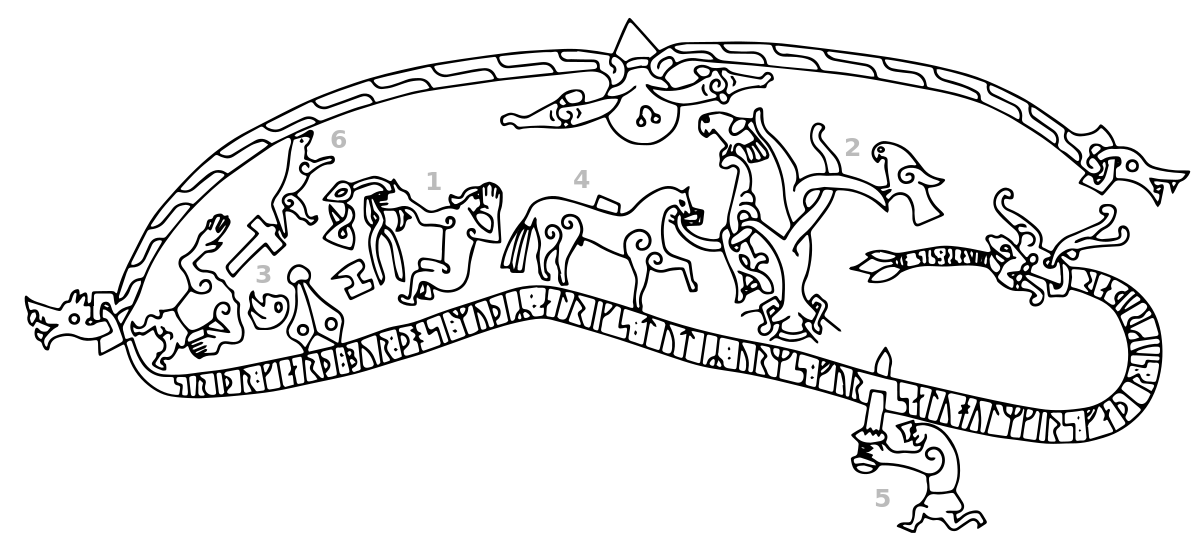

Author and translator Thor Ewing has recently given perhaps the most convincing interpretation to date of the side showing the single human figure at its centre, surrounded by various animals.

He claims that it shows events from the Viking story of Sigurd, told throughout the Scandinavian world. Sigurd was tasked by the blacksmith Regin to kill his brother Fafnir, who had become a fearsome dragon, guarding a huge amount of treasure. After successfully killing the dragon, Sigurd cooked its heart but burnt himself while doing so. While licking his sore fingers, the magic from the dead dragon’s heart enabled him to understand the language of animals. Birds in a tree nearby were discussing how Regin was planning to kill Sigurd and take the dragon’s treasure for himself. (For more on the story and to see some panels that clearly show elements of it, see our page on the nearby Sigurd Cross at Halton).

Does the evidence show that this really does represent the Sigurd story? Above the central human can be seen the definite outline of a dragon’s head, and its faint body depicted as a long serpent-like worm.(Fafnir is often depicted in this form on other ‘Sigurd Stones’ from around the Viking world, and encircling the whole scene, which is the case at Heysham). To kill the dragon, Sigurd hid in a pit and thrust his sword into the dragon when it passed over him. In the carving there is no visible sign of the sword, but this may have eroded away with time, or even have been painted on originally and so no trace now remains. To the left of the Sigurd figure appears to be a tree, with the warning birds beside it. To the right of Sigurd is his horse Grani, looking a little like a camel with a hump. The hump is some of the treasure, and Grani is often similarly depicted this way on other Sigurd stones and crosses.

A comparison with the Ramsund Carving which appears on a flat rock at Sodermanland in Sweden seems to give weight to Ewing’s interpretation. Both the Ramsund Carving and the Heysham Hogback depict Sigurd underneath the dragon Fafnir which encircles the scene. Both have birds and a tree, and Grani the horse with a hump to depict the treasure. The Ramsund Carving also depicts another character named Otr (or Otter) the shapeshifting brother of Fafnir and Regin. Heysham also seems to have him in animal form on the far left side (see the picture above).

Thor Ewing’s interpretation has not been accepted by all scholars, as they say some crucial scenes are missing from the story that are found in other carvings. For example, Sigurd roasting the dragon’s heart, and killing Regin are not there, but both appear on the Halton Cross.

Sigmund and the Wolf

On the top (or roof) of the stone is a depiction of a person lying prone, with an animal at their feet. Thor Ewing interprets this as a scene from the life of Sigmund, Sigurd’s father. In this tale, Sigmund and his nine brothers were taken to a woodland and bound in foot stocks by their sister’s husband. Each night a wolf came to eat one of the brothers. When just Sigmund was left, his sister Signy sent a servant to give him honey to smear on his face and in his mouth. When the wolf returned the next evening it began licking the honey off him. When it tried to lick the honey from within his mouth Sigmund bit hard on the the wolf’s tongue. It immediately pulled backwards, and in doing so broke the wooden stocks, freeing Sigurd who could then make his escape.

More Interpretation Needed

The other main side remains a real mystery. At the centre of the scene is a stag, and surrounding it are four legged creatures, most likely wolves or dogs. Two are flanking the stag, but are facing away from it, as if they are not attacking. A smaller one appears above it, and the remaining two are in distinctly odd positions. One is upside down in the sky, the other is carved vertically, but still with its legs in a walking or running position. There are four human figures standing, two either side of the central animal scene, with their arms aloft.

What is to made of this symbolism? While Thor Ewing’s interpretations of the Sigurd story seem plausible, here he seems less sure. In his account he gives three alternative readings, but none seem very certain. (Readers wishing to learn about Ewing’s thoughts are directed to the Reference section at the bottom of this page where his paper is cited. It can be read for free online and is well worth the time to do so).

Leaving the animals to one side, an interesting interpretation has been offered for the four human figures. The Vikings believed that their first gods killed the giant Ymir and used his body to create the Earth. From his skull they formed the sky. They had four dwarfs hold up the sky, and these were named Austri, Vestri, Nordi and Sudri- or in English – East, West, North and South. Interestingly, in the Heysham scene they do seem to be touching the curve of the sky, perhaps the underside of Ymir’s skull.

In a Viking chieftain’s hall, the four pillars that hold up the main hall beams were often given these same four names of the dwarfs. Here we are reminded of Professor Howard William’s comments that the depictions on a Viking monument can have more than one meaning, if we remember that the shape of the hogback is similar to a Viking hall.

Hogbacks – Interpretation and Inspiration

At Heysham, over a thousand years ago, a locally sourced piece of stone was set up as memorial or grave marker to an important local Viking. Although carved in a fairly crude manner, it is imbued with meaning. All hogbacks are unique in their symbolism. Through a process of historians being willing to try to explain what the symbols mean, and by exposing their ideas to critique from others, progress can be made. This approach, along with comparison to other similarly carved hogbacks, crosses, graves and flat stones around the Viking world will eventually unlock their secrets. The Heysham hogback has been well preserved in St Peter’s church and is available to see on regular open days to the public throughout the year (see the Access section below for details). For more information see the Reference section which lists videos that can be viewed for free by Professor Howard Williams. One is about the Heysham hogback, the other about hogbacks in a wider context.

Today, Heysham has a Viking festival weekend each summer. Directly inspired by the Heysham hogback’s Viking associations, the celebration goes from strength to strength. Demonstrations of Viking tools, artefacts and weapons are on display, along with battle re-enactments and lectures.

Site visited by A. and S. Bowden 2024

Access

St Peter’s Church is usually open on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday 11 am-3pm. See the website here

Heysham Heritage Centre is very much worth a visit. It contains interesting displays and a wealth of books available to purchase. See the website here

Nearby

St Peter’s Church (contains the Heysham Hogback)

Rock-Cut Graves and St Patrick’s Chapel

A Drive Away

Bolton-le-Sands Viking Age Stones

Holy Trinity Church Bolton-le-Sands

Bolton-le-Sands Free Grammar School

References

Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture: Cheshire and Lancashire Volume IX, Richard N. Bailey (2010) The British Academy. This fantastic volume can also be viewed online, for free: chacklepie.com/ascorpus/catvol9.php?pageNum_urls=114

Citations in Stone : The Material World of Hogbacks, Howard Williams (2016) European Journal of Archaeology 19 (3): 400-14

Understanding the Heysham Hogback : A tenth century sculpted stone monument and its context, Thor Ewing. Available for free at hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/152-2-Ewing.pdf

What we don’t know about the Heysham hogback Professor Howard Williams at the Heysham Viking Festival 15th July 2017. Lecture available online: vimeo.com/225900707

Viking Age Hogback Stones : Citations and Exceptions, SCA Lecture Professor Howard Williams. Lecture available online: youtube.com/watch?v=-S0ZHLl0278

howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2021/06/04/viking-age-hogback-stones-citations-and-exceptions/

howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2017/07/19/the-heysham-hogback-part-2/

howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2017/07/04/the-heysham-5-hogback/

jonaslaumarkussen.com/illustration/the-ramsund-carving-so-101/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigurd_stones

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigmund

kids.britannica.com/students/article/Ymir/314290

Comments are closed.