On the headland above Heysham village lie stunning rock-cut graves, close by the ruin of St Patrick’s Chapel. The chapel itself is a very rare survivor of an early Saxon church in Lancashire. Together with the spectacular views overlooking Morecambe Bay to the hills of Cumbria, the site is as awe-inspiring today as when it was first constructed well over a thousand years ago.

There are two sets of rock-cut graves, one group of six and a second group of two. Neither are aligned with the chapel, leading the archaeologists who dug the site to believe that they were created before the chapel was built.

The six rock-cut graves lie on the western edge of the site, carved directly into the millstone grit bedrock. Five of them have a socket at their head, into which a cross would have been inserted. These crosses would have been made of stone, elaborately carved, and possibly painted. Heavy grave slabs would have covered the rock indentations. Though some have the shape of a body, they are thought to be too shallow to contain full adult skeletons. It is likely that they acted as shrines for selected revered bones, perhaps some of them were even believed to contain the remnants of saints. Whatever they were, they were unquestionably of high status.

The second group of two rock-cut graves is found in an area that would much later become a cemetery around the chapel. One of the graves also has a cross socket at the head of it, the other does not. The fact that they deviate from the normal Christian east-west orientation means they could be even earlier than the set of six.

A single cross socket without a grave lies underneath the place where the chapel now is. In all likelihood this would have held a preaching cross for the site. This cross, together with the two sets of rock-cut graves, would have been in use by the late 600s to early 700s. The site was a place of worship, and probably attracted pilgrims too.

St Patrick’s Chapel

The chapel was built some time in the 700s. Initially, it was a small building just four metres in length. To lay a level foundation over the irregular bedrock, the ground was first covered with stones, sand and mortar. Flagstones were placed on top of this base and these were covered by puddled clay. Both the interior and exterior walls were covered in a lime-based plaster, which had a finishing coat of lime wash placed over it. The wash provided a surface on which paint was applied to the inside of the chapel.

Archaeological evidence from the site shows that red ochre, yellow ochre and a greenish-brown pigment (derived from burnt vegetable matter) were used as paints. Most intriguingly, two fragments of plaster bear the letters MV and LIE, written in red ochre against a white background. They may or may not have once been connected, but if they were they would spell out MVLIE – in Latin ‘mulie’- meaning ‘woman’. The lettering could have been free-standing text painted on the wall, or a label for figures, or comments on a wall scene. Expert analysis of the letters show that they were close in style to other Anglo-Saxon examples of the time, but not like that used in the Irish Celtic church, which also had considerable influence in Britain at the time.

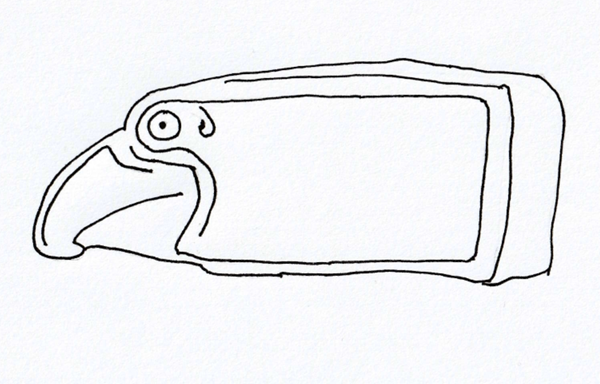

A large stone carving of a bird’s head, dating from the late 600s to 700s, was discovered during excavation. There has been much speculation as to its origins by historians. The two main schools of thought put forward are that it was either part of a shrine or a piece of a high status reading chair. It is the chair idea that has been most widely accepted. Images of these are seen in illustrated manuscripts such as the Book of Dimma and MacRegol Gospels. Birds’ heads feature in such chairs as either arm rests or at the top of a high back rest. However, despite being such a well-made and important item used within the chapel, it was later utilised in a rather ignominious way.

Drawing by the author

The Chapel is Extended

In the second phase of building, the chapel was doubled in length to extend to almost eight metres long, which is the present length. The north-east corner was positioned right on the edge of the cliff, with huge stones known as quoins strengthening the corners of the building. The south doorway, still in place today, was created using the curved stone lintels from a previous doorway. Plaster was stripped from original inner walls and some of it ended up in the rubble part of the floor, which formed a demolition layer, raising the floor level by half a metre.

A New Cemetery is Added

Some time in the 900s, lay members of the community began to be buried around the sides of the chapel. Archaeologists found that the cemetery was split into a large central area with two smaller sites in the east and west. Bodies were placed on their backs, in a traditional Christian east-west orientation (with their heads pointing towards the west). Some had their arms crossed, which was also an early Christian practice. A mix of women, men and children were interred. Perhaps surprisingly, ten people, two of which were children, were buried under the floor of the chapel itself.

The central cemetery was developed in a natural gulley. Four stone steps, still present and very worn, could have lead down to a gate in a surrounding wall. Excavation discovered fifty-two graves, none of which were cut into the bedrock. Instead a rubble layer was placed over the bodies. Of particular significance was the burial of a woman who was placed close to the south door of the chapel. She had been wrapped in a shroud and to the right side of her pelvis was a curved ‘hogback’-shaped bone comb of Anglo-Scandinavian design.

The comb was made of cow bone, with ten ‘teeth plates’ (individual pieces into which had been carved teeth). Two flat ‘handles’ either side of the plates held the teeth plates in place, and six iron rivets bound the whole thing together. The approximately seventy teeth showed little wear, but three were missing and another was broken. The archaeologists noted that the woman had her arms crossed in the Christian fashion, but that the inclusion of a comb was a common marker of Viking graves. The fact that Heysham has a Viking age hogback stone in nearby St Peter’s Church clearly points to an influx of people from the Norse culture. It is not uncommon to see Vikings embrace the Christian tradition and a mix of the two cultures in their beliefs, as the Sigurd Cross at nearby Halton shows.

The East and West Cemeteries

The east cemetery contained thirteen burials, five of which were stone-lined and also covered over with stones. It was here that the above described stone bird’s head carving was discovered. It had been placed at the head of one of the burials, face down, to form part of the lining of the grave. Re-use of such a high status item in such a manner begs the question of what happened to the chair. Was it broken, and so had just become building material, or did fashions drastically change?

The west cemetery was situated in a small hollow. Like the east cemetery, this had thirteen burials but in two distinct phases. Here the graves were lying on bedrock, and the lack of soil may have necessitated the construction of stone tombs. One well-constructed tomb had two male burials in it (from different times) and a similarly impressive one contained a woman.

Into the Twentieth Century

In 1903, the foundations of St Patrick’s Chapel were strengthened and its masonry repointed. The coping stones on the top part of its wall were repaired. However, within a few decades it was once again in poor repair. This was from a combination of it being constantly exposed to severe winter storms and, being a completely open site, it was also subject to vandalism. Fragments of human bones were becoming exposed in the cemetery area.

A four-week excavation was begun in April 1977 by Lancaster University. The dig was supervised by R.D. Andrews under the direction of Timothy Potter. A second season followed during the subsequent spring. A large-scale survey took place of the ruined chapel and the cemetery area of the surrounding headland and nearby St Peter’s church. Repair work was carried out on the chapel. The bones were all removed from the site and subjected to analysis.

The bones from both the cemetery and from within the chapel were in poor condition due to the exposed nature of the site. The radiocarbon dates showed a date range from 940 to 1185. The total number of individuals was calculated by counting the upper arm and upper and lower leg bones. Around eighty-four individuals from the community were buried on the site during its use, with a fairly even split between males and females. This included sixty-five adults and nineteen children under the age of fifteen. Less than ten percent of the adults had lived beyond the age of forty-five, but this would be fairly normal at the time. Osteoarthritis was present in twenty-four individuals, but interestingly only five people showed signs of bone damage from very hard work. The bones were subsequently reburied in St Peter’s churchyard.

Unanswered Questions

While excavation and ongoing research has yielded up many of the mysteries of the rock-cut graves and St Patrick’s chapel, some large questions remain. Why is the chapel dedicated to St Patrick, and what is its association with St Peter’s Church, which stands just a stone’s throw away from it?

It is not known where or when St Patrick was born but, from his writings, historians place him sometime in the 400s. In recent years, two places have been put forward for his place of origin, both based around Romano-British settlements. These are Ravenglass in Cumbria and Birdoswald near Hadrian’s Wall – both places with Roman forts that continued to have civic importance after the Romans left. His writing states that he was kidnapped by Irish pirates. After six years in Ireland he escaped, and returned to England. It’s not clear where he made landfall – local tradition holds that it was at Heysham, but there is no documentary evidence to back this up.

His existence is over two hundred years before the establishment of the rock-cut graves and chapel, clearly a long time. However, was tradition strong enough to lead people to believe that he had returned to England at this spot? Furthermore, could the church have claimed to hold his bones in a reliquary at the rock-cut graves? The truth of such a claim may not have mattered – if people believed that a saint’s bones were there, this would make the site a place of pilgrimage and a source of revenue for the church. It is clear that the occupants of the rock-cut graves were of very high status. They could have been venerated priests or monks, but perhaps there were claims for saints’ bones as well, St Patrick’s amongst them.

The existence of both St Patrick’s and St Peter’s in such close proximity is also perplexing. St Peter’s church has survived intact, and the architecture clearly reveals it was in use in Saxon times, at the same time as people were being buried in St Patrick’s cemetery above. As noted previously, few bodies in St Patrick’s burial areas showed little evidence of hard life (beyond osteoarthritis). Were these people spared the physicality of daily labour, having a higher status than those buried below in St Peter’s? It has not been possible to compare the skeletons in St Peter’s as this is a graveyard in continuous use and, as a consecrated space, the bodies cannot be dug for archaeological comparison. Eventually, St Patrick’s was abandoned, but St Peter’s has continued in use as a place of worship right up to the present day.

Visiting Today

Visitors today can marvel at the views and the two sets of rock-cut graves. The ruined chapel is well preserved. Its east wall is almost fully intact and, at just two and a half metres wide, it gives a sense of how narrow the chapel was in both its shorter and longer incarnations. A fragment of the north wall remains, attached to the east one. The south wall contains a doorway with distinctive arches on each side, and the lower part of a narrow window.

Two grave slabs lie in the central area where the cemetery once was. One is a full length relief (or raised) cross. Dating from the 800s, it has no parallels in the north-west of England, but similar ones are found at Lindisfarne and Durham in the north-east. The grave slab next to it is also a relief cross, but very eroded now. This has been given a later date of around 1000s. Neither are in their original positions.

A number of pathways lead from around the headland. There are routes down to the beach and to the area known as Barrows Field where a large amount of tiny stone chippings have been found, created by hunters in the Mesolithic (Middle Stone) Age. It seems that this was a major hunting base, occupied all year around.

Below the headland lies St Peter’s church and graveyard. This church has its own wealth of history, including the stunning Heysham Hogback Viking age monument.

Site by visited by A. and S. Bowden 2024

Access

The site is open access. There is a large car park at the bottom of Heysham village. Walk up the historic main street to St Peter’s Church. Then follow the path up to the headland to view the rock-cut graves and ruins of St Patrick’s.

If visiting Heysham, call in at the Heysham Heritage Centre to see information displays, leaflets, books and gifts. See their website here

Nearby

A Drive Away

Bolton-le-Sands Viking Age Stones

Holy Trinity Church Bolton-le-Sands

Bolton-le-Sands Free Grammar School

References

Excavation and survey at St Patrick’s Chapel and St Peter’s Church, Heysham, Lancashire, T.W. Potter and R.D. Andrews. Available as a free pdf at lahs.archaeologyuk.org/Contrebis/21_29_Potter.pdf

Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain, George Nash (2008) Time and Mind November 2008. Available at Researchgate.net

Heysham: Two Ancient Churches and a Burial Ground, A.J White (2003) Lancaster City Museums

howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2017/05/09/st-patricks-chapel-heysham/

historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1020535?section=official-list-entry

cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/st-patrick-was-cumbrian-background-waterhead

Comments are closed.